-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Kelley Lee, Global health promotion: how can we strengthen governance and build effective strategies?, Health Promotion International, Volume 21, Issue suppl_1, December 2006, Pages 42–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal050

Close - Share Icon Share

SUMMARY

This paper discusses what is meant by ‘global health promotion’ and the extent to which global governance architecture is emerging, enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health within an increasingly global context. A review of selected initiatives on breast-milk substitutes, healthy cities, tobacco control and diet and nutrition suggests that existing institutions are uneven in their capacity to tackle global health issues. The strategic building of a global approach to health promotion will draw on a broad range of governance instruments, give careful attention to implementation in the medium to longer term, reflect on the nature and appropriateness of partnerships and develop fuller understanding of effective policies for harnessing the positive influences of globalization and countering the negatives.

INTRODUCTION

As globalization increasingly impacts on diverse aspects of our lives, we are beginning to understand how factors that go beyond the national borders of individual countries are influencing the determinants of health and health outcomes. This paper discusses what is meant by ‘global health promotion’ in terms of the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health (WHO, 1986) within an increasingly global context. The focus of this paper is the extent to which global governance architecture is emerging for health promotion. After briefly reviewing the concepts of global health governance (GHG), this paper draws lessons from selected examples of global health promotion initiatives and concludes with suggested strategies for building a global approach to health promotion.

FROM INTERNATIONAL TO GLOBAL GOVERNANCE FOR HEALTH PROMOTION

Governance concerns the many ways in which people organize themselves to achieve common goals. Such collective action requires agreed rules, norms and institutions on such matters as membership within the cooperative relationship, distribution of authority, decision-making processes, means of communication and resource mobilization and allocation. Health governance concerns the agreed rules, norms and institutions that collectively promote and protect health (Dodgson et al., 2003).

Importantly, while government can be a central component of governance, governance more broadly embraces the contributions of other social actors, notably civil society organisations (CSOs) and the corporate sector. Moreover, governance embraces a variety of mechanisms, both formal (e.g. law, treaty and code of practice) and informal (e.g. norms and custom) (Finkelstein, 1995). Formal instruments with the strongest regulatory powers can be legally binding and backed by punitive measures (e.g. fines or imprisonment). Informal mechanisms may rely on self-regulation and voluntary compliance, as well as less tangible forms of censure, such as public opinion.

Global health governance GHG can be distinguished from international health governance (IHG) in three ways. First, IHG involves crossborder cooperation between governments concerned foremost with the health of their domestic populations. Infectious disease surveillance, monitoring and reporting, regulation of trade in health services and protection of patented drugs under the Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) are examples of IHG. However, changes being brought about by globalization mean that many health determinants and outcomes are becoming increasingly difficult to confine within a given territorial boundary (i.e. country) and, in some cases, are becoming de-linked from physical space (deterritorialised) (Scholte, 1999). As such, it has been argued that the current IHG architecture alone is inadequate to deal with transborder flows that impact on health, such as people trafficking, global climate change and internet pharmaceutical sales (Lee, 2003).

Second, the mechanisms of IHG are, by definition, focused on governments in terms of authority and enforcement. Examples include the International Health Regulations (IHR) and Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). In contrast, GHG embraces both governmental and non-governmental actors and a wider range of formal and informal governance mechanisms. These include voluntary codes of practice, quality control standards, accreditation methods and consumer monitoring and reporting. These mechanisms vary widely in their jurisdiction, purpose, scope and associated resources.

Third, while IHG is traditionally focused on the health sector, GHG seeks to address the broad determinants of health, extending its reach to health impacts from non-health sectors, such as trade and finance, and environment across multiple levels of governance. As Collin et al. (Collin et al., 2005) write,

The three distinct features of GHG described above can be understood through the example of efforts to control dengue fever across multiple countries. An IHG approach would concentrate on a coordinated effort by ministries of health in affected countries to tackle environmental factors (e.g. spraying and reducing potential breeding sites), distribute bed nets and increase the use of insect repellents. Reporting of data on incidence might be shared among the appropriate public health authorities. In contrast, a GHG approach would consider the role of transborder factors, such as documented and undocumented migration, and migration of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. In addition to government, there might be cooperation among a wide range of relevant stakeholders such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), private companies, research institutions and local communities. Finally, the impacts on the social and natural environment from changes to agricultural practices (e.g. agribusiness), terms of trade, or conflict and political instability would be taken into account.In a world where many health risks and opportunities are becoming increasingly globalised, influencing health determinants, status and outcomes cannot be achieved through actions taken at the national level alone. The intensification of transborder flows of people, ideas, goods and services necessitates a reassessment of the rules and institutions that govern health policy and practice.

To the extent that globalization requires global governance architecture for health, there is a need to rethink traditional approaches to health promotion. There is a need to understand how globalization, defined as changes that are intensifying crossborder and transborder flows of people and other life forms, trade and finance and knowledge and ideas, is impacting on the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health. For example:

The promotion of sexual health may require greater attention to changing patterns of population mobility within and across countries in the form of migration, tourism, displaced populations and migrant workers.

The promotion of healthy diets may require measures to counter the marketing of global brands by transnational corporations.

The promotion of tobacco control may require measures to tackle the availability of contraband cigarettes, and the targeting of emerging markets in low-and middle-income countries by transnational tobacco companies (TTCs).

The promotion of healthy living environments may require greater attention to the impact of large-scale agricultural production on urbanization and land availability.

In summary, global health promotion can be defined as the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health within an increasingly global context. The challenge lies in creating effective forms of governance that support such efforts. In principle, there is an emergent architecture for global health promotion, as shown in the examples below. By definition, health promotion is broadly conceived to involve a range of social institutions, from governmental bodies to individual families. In practice, however, initiatives to date that seek to tackle global health issues have reflected the uneven quality of existing institutions and shortfalls in how they operate together. In briefly reviewing these examples, particular attention is given to the institutions and mechanisms involved, the effectiveness of these efforts (strengths and weaknesses) and lessons learned for future action.

LESSONS TO DATE: SELECTED EXAMPLES OF GLOBAL HEALTH PROMOTION

International code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes

Adopted in May 1981 by WHO member states, following years of concern about the general decline in breastfeeding in many parts of the world, the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes represented the culmination of a prominent global health promotion campaign by WHO, UNICEF and NGOs led by the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN). The code was highly successful at drawing worldwide public attention to the health consequences of the marketing practices of infant formula manufacturers, with NGOs mounting a successful boycott of Nestlé. Despite non-support by the US government, the code was adopted by national health systems around the world and corporations were made acutely aware of the power of consumer action.

The implementation of the code during the past 20 years has seen mixed success. Despite the high-profile adoption of the code, and efforts in some countries to align national law to its provisions, it remains largely a voluntary code. Widespread violations in many low-and middle-income countries have been reported (Taylor, 1998), and there remain few formal means of enforcement beyond public censure. Efforts to raise the issue within the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Codex Alimentarius, World Trade Organization (WTO) and other relevant international forums have sought to embed the code within nutritional guidelines and trading principles. Amid a renewed Nestlé boycott, NGOs also accuse the company of engaging in new marketing tactics to circumvent provisions, including the use of a corporate social responsibility initiative (i.e. ombudsman scheme) to placate public concerns. Meanwhile, NGOs monitoring companies report that 4000 babies continue to die each day from unsafe bottle feeding (International Baby Food Action Network, 2004).

This example suggests that reliance on voluntary codes alone to regulate the behaviour of powerful and well-resourced transnational corporations, without sufficient attention to implementation and enforcement, is likely to be ineffective. While NGOs can effectively campaign to draw public attention to an issue, public pressure can be difficult to sustain in this way in the longer term without the support of more formal governance instruments. This is especially so given the worldwide scale of the issue. A voluntary code can be seen as an initial effort to raise awareness and improve public education. If ongoing monitoring shows non-compliance (Allain, 2002), stronger governance instruments may be necessary in time.

Healthy cities programme

The idea of ‘healthy cities’ took off in the mid-1980s, following a Canadian conference ‘Beyond Health Care Conference’ that focused on community health promotion. The idea was quickly taken up by WHO which launched an initiative in 1988 to protect and promote the health of people living in urban environments. With over half the world's population living in large cities and towns by 2007, and rapid urbanization continuing apace, the Healthy Cities Programme soon became a worldwide movement.

The Healthy Cities Programme is widely described as a success story. Each phase of the movement has seen a steady increase in the number of supporting cities to over 3000 worldwide in 2003. Regional networks, in turn, have also been formed to support the work of local communities. This is reinforced globally by the International Health Cities Foundation and an international conference held regularly since 1993. The distinct features of the Healthy Cities movement, in terms of governance, have been its holistic approach to health promotion and its partnerships with a diverse range of actors at multiple policy levels. Building on the principles of Health for All, and the concept of environmental sustainability, the initiative recognizes that:

Based on this vision, WHO set a common agenda that could be used for promoting local action by individuals, households, communities, NGOs, academic institutions, commercial businesses and governments.A healthy city is one that is continually creating and improving those physical and social environments and expanding those community resources which enable people to mutually support each other in performing all the functions of life and in developing to their maximum potential (Hancock and Duhl, 1988).

While Healthy Cities has proven effective at mobilizing diverse interests around an agreed health goal, Awofeso (Awofeso, 2003) argues that this success so far ‘has largely been confined to industrialized countries’. It is argued that larger scale health risks such as poverty, urban violence and terrorism, skeletal urban infrastructure in poor countries, and impacts of ‘capitalist globalization’ have as yet been inadequately addressed. Moreover, the evidentiary base and generalizability as a global movement to local contexts remain unclear. As such, Awofeso concludes that the ‘Healthy Cities approach is unlikely, in its present form, to remain a truly effective global health promotion tool this decade’.

This example suggests that global health promotion can be successfully initiated with a clear and shared vision and effectively built through engagement with relevant stakeholders. Unlike the baby milk code, powerful vested interests were not overtly challenged in this case. Achieving truly global impact, however, may require careful reflection on its relevance to diverse and underserved populations. A further progression of the movement might then be launched, with adapted evidence-based goals, resources and actions.

Framework convention on tobacco control

The scale of the emerging tobacco pandemic (predicted 10 million deaths annually by 2030) led WHO to initiate the FCTC in 1998. While ostensibly an international treaty between national governments, the increasingly global nature of the tobacco industry and the consequent shift of the health burden to ‘emerging markets’ in the developing world (70% of expected deaths by 2030) convinced WHO of the need for a global approach to health promotion. As Yach (Yach, 2005) describes, ‘The rationale for the FCTC was to address the transnational aspects of tobacco control as it strengthens and stimulates national actions. Issues such as illicit trade, controls on cross border marketing and international norms for product regulation…’ Similarly, the then WHO Director-General Gro Harlem Brundtland (Brundtland, 2000) stated,

One of the key governance innovations during the negotiation and implementation process has been the contribution of civil society groups. These inputs have been largely organized around the Framework Convention Alliance, aThe Framework Convention process will activate all those areas of governance that have a direct impact on public health. Science and economics will mesh with legislation and litigation. Health ministers will work with their counterparts in finance, trade, labour, agriculture and social affairs ministries to give public health the place it deserves. The challenge for us comes in seeking global and national solutions in tandem for a problem that cuts across national boundaries, cultures, societies and socio-economic strata.

As well as accelerating accreditation of NGOs with ‘official relations with WHO’, the scope of involvement widened to allow access to open working groups. Perhaps more important than the formal terms of participation has been the ability of NGOs to play a number of key supporting roles. These include informing delegates (e.g. seminars and briefings), lobbying, publishing reports on key issues (e.g. smuggling) and even serving on national delegations.heterogeneous alliance of non-governmental organizations from around the world who are working jointly and separately to support the development, signing, and ratification of an effective Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and related protocols. The Alliance includes individual NGOs and organizations working at the local or national levels as well as existing coalitions and alliances working at national, regional, and international levels (Collin et al., 2005).

The focus since the FCTC came into effect in February 2005 has been on subsequent implementation within countries. The evidence to date suggests that the treaty, so far signed by 192 countries and ratified by 60, has been an effective catalyst for putting tobacco control much higher than ever before on policy agendas in many countries. The sustained effort to achieve this over the past seven years, culminating in the FCTC, has more recently been followed by a potential decline in interest due to a perception that tobacco control is now ‘done’. With individual protocols to negotiate and the actual implementation of policies in member states, the task is clearly far from complete.

The decision by Gro Harlem Brundtland to step down as WHO Director-General in 2003, after a single term, has invariably meant a loss of global leadership on the issue, despite reassurances by her successor, the late J. W. Lee, that tobacco control remains a high priority. Tobacco control advocates worldwide now face the challenge of keeping the attention of the donor community from shifting to the next ‘priority’ on an already crowded global health agenda.Unfortunately, governments and international agencies run the risk of becoming complacent. For many, the FCTC is done, tobacco control has an answer and the rest will follow. Nothing could be more dangerous than that premise. In fact, if we are not alert and active, the FCTC could turn into yet another treaty gathering dust in ministries and academic institutions around the world (Yach, 2005).

This example suggests that, like the Healthy Cities Programme, a worldwide health promotion movement requires strong high-level leadership and clearly defined goals. WHO was successful, perhaps even more so than for the baby milk code, in taking on a powerful industry despite strong opposition from vested interests. The role of civil society was critical to the FCTC negotiation process, mobilized into an effective global social movement. Efforts were made to include pharmaceutical companies (manufacturers of nicotine replacement therapy), although involvement by the tobacco industry itself was restricted to submissions to public hearings along with other stakeholders. The industry's production and marketing of tobacco as harmful products, its rapid and unapologetic spread into ‘emerging’ markets, along with evidence of covert efforts to undermine WHO and the FCTC process, precluded the acceptability of ‘partnership’. How sustainable the FCTC will be, as a pillar of GHG around which governmental organizations and NGOs can rally, will depend on the degree to which this global initiative can now become entrenched in regional, national and local level institutions.

Global strategy on diet and nutrition

Lessons learned during the FCTC negotiations have begun to be applied to tackle another major contributor to the looming non-communicable disease burden (60% of deaths worldwide)—poor diet and nutrition. Similar to tobacco control, health promoters face powerful vested interests who dominate world food production and consumption. A draft WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health, endorsed by the WHA in 2004, was supported by a range of organizations including the International Union Against Cancer (UICC), International Diabetes Federation and World Heart Federation. However, the US government, reportedly under pressure from the domestic food lobby led by sugar producers, argued against stronger regulation, citing the importance of individual responsibility for lifestyle choices.

The document eventually adopted in May 2004 was described as ‘a milder final draft’ resulting from ‘a diplomatic high-wire act to silence its critics and win worldwide support’ (Zarcostas, 2004). In defending its need to consider almost 60 new submissions, WHO officials described the need for a ‘balanced’ approach that ‘takes into account political realities’ (Zarcostas, 2004). While parallels were drawn with the FCTC, as Yach Yach, 2003 stated, ‘food is not tobacco. The food and beverage industries are a part of the solution’. Fuelling the political battle has been a perception of scientific uncertainty. Despite alarming upward trends in obesity and diet-related ill-health, the evidentiary base for underpinning global guidelines on diet and nutrition has remained keenly fought over. The multiplicity of factors contributing to poor diet and nutrition, and the need for a better understanding of what policy interventions are most effective to address them, has made policy discussions fraught with complexity compared to tobacco control. This task has been made more difficult by industry-funded claims that recommended daily intakes of salt, sugar and fat are unnecessary. As Yach et al. (Yach et al., 2005) advise, ‘Undertaking research necessary to close the remaining knowledge gaps is therefore important to eliminate any persistent uncertainty, particularly with regard to the health effects of obesity’.

The ongoing tussle over a global dietary strategy contrasts with the Move for Health Initiative adopted by the World Health Assembly (WHA) in 2002 to promote increased physical activity. Described as ‘driven by countries’, implementation has sought to involve a wide range of ‘concerned partners, national and international, in particular other concerned UN Agencies, Sporting Organizations, NGOs, Professional Organizations, relevant local leaders, Development Agencies, the Media, Consumer Groups and Private Sector’ (WHO, 2003). The initiative is described as offering core global messages to partner organizations, but allowing flexible implementation at local, national and regional levels.

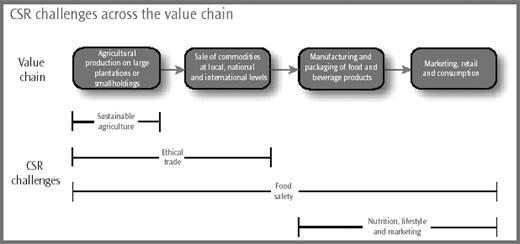

Importantly, unlike the FCTC and guidelines on diet, this initiative does not face strong vested interests in the same direct way. This has allowed public health organizations to engage a wider range of partners than available to tobacco control advocates, for example. Indeed, many private companies have begun to support the initiative, possibly as a means of demonstrating corporate social responsibility (Figure 1), but ostensibly to prevent stronger regulation and product liability litigation (Mello et al., 2003). Such ‘partnerships’ have not been without criticism. In the UK, with the fastest growing obesity rates in Europe, it was reported that the food industry agreed in 2004 to contribute millions of pounds to the creation of a National Foundation for Sport ‘if they want to avoid stricter regulation’ of food advertising, marketing and labelling (Winnett and Leppard, 2004). The supermarket chain Sainsbury's has introduced the Active Kids voucher scheme to provide schools with sports equipment. However, Cadbury's Get Active initiative, supported by the British sports minister, has been criticized for requiring schoolchildren to spend over £2000 on chocolate (almost one and a quarter million calories) to earn a set of volleyball posts (Food Commission, 2003). The use of sports personalities to promote unhealthy food options has also been criticized.

Corporate social responsibility challenges across the food and beverage industry value chain. Source: Prince of Wales International Business Leaders Forum, Food for Thought: Corporate social responsibility for food and beverage manufacturers. London, 2002.

This example suggests that global health promotion on diet and nutrition faces difficult challenges. It must improve the evidentiary base and build necessary but appropriate partnerships with the food and beverage industry. The public health community should be aware of strategies to undermine such efforts by vested interests, with some parallels to the FCTC process. Nonetheless, there are limitations to applying the interventions used in tobacco control to a global strategy on diet. Most notably, tobacco is inherently harmful to health, while food intake is necessary to life. Excluding the food and drink industry from policy development and implementation would therefore seem inappropriate. Fuller understanding of effective health promotion activities is needed, accompanied by efforts to build a broad global network of supporting institutions, with clearly agreed criteria of acceptable collaboration.

STRATEGIES FOR BUILDING A GLOBAL APPROACH TO HEALTH PROMOTION

This brief overview of global health promotion offers a number of lessons for future action.

First, a global approach to health promotion should seek to draw on a wide range of governance instruments, from voluntary codes to binding legislation. Not all of these instruments will be available at various policy levels. For instance, legally binding regulations at the regional and international level require careful negotiation vis-à-vis principles of state sovereignty. Where agreement to binding measures are not possible, ‘softer’ forms of governance (e.g. declarations of principles or codes of practice) may need to be relied upon to draw public attention to an issue, lend symbolic value to a health promotion movement or serve as the basis for public education. In some cases, stronger regulatory measures may unavoidably be needed, with ‘teeth’ to ensure compliance, when dealing with strong vested interests. Moreover, different instruments or combinations of instruments will be appropriate for different contexts and at different points in time.

Second, ensuring the effectiveness of governance instruments for global health promotion requires careful attention to implementation in the medium to longer term. High-profile global initiatives are increasingly numerous, but have stumbled over insufficient attention to ensuring sufficient capacity, political will, resources and leadership to implement from the local level upwards. The ‘eight capacity wheel’ (Catford, 2005) for assessing national capacity for health promotion, supported by the Bangkok conference, suggests stark shortfalls in many countries, as well as at the global level. The existing picture is highly fragmented. If global health promotion initiatives are to prove effective, far greater attention to supporting them through skilled personnel, an authority base and social agreement about the need and approaches for implementation are essential.

Third, careful reflection on the nature and appropriateness of partnerships for global health promotion is needed. In principle, ‘broad based, well networked, vertical and horizontal coalitions’ (Yach et al., 2005) are intuitively attractive. The building of ‘partnerships’ for global health promotion across a broad spectrum of institutions and interests has been an important and popular development (Wemos Foundation, 2004). However, the process of formulating such partnerships requires critical reflection. Partnerships can become overly inclusive, hampered by complex working relationships and an insufficient basis for working together. Conversely, partnerships can be too exclusive, failing to recognize the need for a broad social movement or policy advocacy. The abundance of partnerships created to date offer fertile ground for drawing wider lessons. For example, Thomas and Weber (Thomas and Weber, 2004) describe recent efforts to mobilize global resources for HIV/AIDS as ‘focused on piecemeal investments based on loans, discounts, or donations’.

In other words, if partnerships are critical to addressing the challenges posed by globalization to health, there is a need to understand when such partnerships are appropriate, what the membership should be, how partners should work together and what governance instruments are needed to regulate them.The piecemeal approach…is often presented in the language of partnerships. A key problem with these ‘partnerships’ is that they are not based on substantive conceptions of equality that underpin, for instance, the health for all ideal, and that those in whose interests they are avowedly developed are in general excluded from their negotiation. For serious partnerships to develop, developing countries must be fully involved in deliberations with companies and UN organizations.

Fourth, there is a need for better understanding of effective policies for harnessing the positive influences of globalization, and countering the negatives. This must be based on better knowledge of the interconnections between global (macro) level influences and everyday lives at the individual and community levels. This should include understanding of the ways global forces influence decisions about lifestyle and health. This is well understood, for example, by large transnational corporations employing powerful marketing techniques to build global markets (e.g. branding and sponsorship). Health promotion policies could harness such strategies and use them to create counter influences.

Fifth, and related to the above points, there are a number of research areas that require attention to underpin a global approach to health promotion.

A fuller assessment of what governance instruments have been used, in what contexts, and their degree of effectiveness than can be provided in this brief analysis is needed. When is it necessary and possible to apply certain instruments? Should instruments used be changed over time and when is this appropriate?

The ingredients for effective implementation of global health promotion initiatives require fuller understanding. What does capacity for global health promotion mean in terms of resources, skills, leadership and political will? How can we build capacity for global health promotion at various levels of health governance?

A critical review of partnerships for global health promotion is needed. What partners are (in)appropriate for which issues? What roles should partners play in such collaborations? How can partnerships improve their transparency and accountability?

A broader review of how well health governance is working to address the challenges of globalization is needed. While there has been some limited analysis of specific governance mechanisms, an overall assessment of the system as a whole (GHG architecture), and how it can be improved, is needed to take account of significant governance changes since the early 1990s.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author wishes to thank Professor Vivian Lin for her helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper and the members of the Conference Organizing Committee for their inputs.