Abstract

Objective:

To assess factors associated with exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in Accra, Ghana.

Design, subjects, setting:

Data on current and past infant feeding patterns, sociodemographic, biomedical and biocultural factors were collected using a cross-sectional design, from a sample of 376 women with infants 0–6 months, attending maternal and child health (MCH) clinics in Accra. EBF was defined in two ways: (a) based on a 24-h recall, and (b) based on a recall of liquids or foods given since birth.

Results:

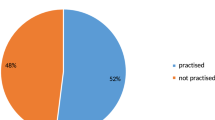

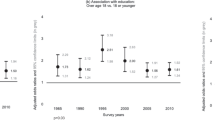

Although 99.7% of mothers were currently breastfeeding (BF), only half (51.6%) of them EBF their infants. About 98% of participants had heard about EBF, and 85.6% of them planned to EBF on delivery. Based on ‘since birth’ EBF, planned EBF on delivery was associated with higher likelihood of EBF (OR=2.56; 95% CI, 1.06–6.17) and delivery at a hospital/polyclinic was associated with a two times higher likelihood of EBF (OR=1.96; 95% CI, 1.08–3.54). Women living in their own houses were more likely to EBF (OR=3.96; 95% CI, 1.02–15.49) than those living in rented accommodations and family houses. Those with a more positive attitude towards EBF were more likely to EBF (OR=2.0; 95% CI, 1.11–3.57) than their counterparts with more negative attitudes. The ‘24-h recall’ EBF model yielded similar results.

Conclusion:

In this population, EBF was associated with delivery at hospital/polyclinic, having secondary school education, intention to EBF prior to delivery, owning a home and having a positive attitude to EBF.

Sponsorship:

Funded by a University of Connecticut Research Foundation grant awarded to Dr Rafael Pérez-Escamilla, and the LINKAGES program, Accra, Ghana.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Anderson JW, Johnstone BM & Remley DT (1999): Breastfeeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin . Nutr. 70, 525–535.

Arifeen S, Black RE, Antelman G, Baqui A, Caulfield L & Becker S (2001): Exclusive breastfeeding reduces acute respiratory infection and diarrhea deaths among infants in Dhaka slums. Pediatrics 108, 1–8.

Beaudry M, Dufour R & Marcoux S (1995): Relation between infant feeding and infections during the first six months of life. J. Pediatr. 126, 191–197.

Brown KH, Black RE, de Romana GL & de Kanashiro HC (1989): Infant-feeding practices and their relationship with diarrhoeal and other disease in Hauscar (Lima) Peru. Pediatrics 83, 31–40.

Cohen R, Brown K & Canahuati J (1994): Effects of age of introduction of complementary foods on infant breast milk intake, total energy intake, and growth : a randomised intervention study in Honduras. Lancet 344, 288–293.

Dearden K, Altaye M, de Maza I, de Oliva M, Stone-Jimenez M, Morrow AL & Burkhalter BR (2002): Determinants of optimal breastfeeding in peri-urban Guatemala City, Guatemala. Pan. Am. J. Public Health 12, 185–192.

Dewey KG, Cohen R, Brown K & Rivera LL (1999): Age of introduction of complementary foods and growth of term, low-birth-weight, breastfed infants: a randomized intervention study in Honduras. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 69, 679–686.

Dibley MJ, Goldsby JB, Staehling NW & Trowbridge FL (1987): Development of normalized curves for the international growth reference: historical and technical considerations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 46, 736–748.

GSS & MI (1999): Ghana Demographic and Health Survey 1998. Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and Macrointernational (MI), Calverton, Maryland.

Heinig MJ & Dewey KG (1996): Health advantages of breastfeeding for infants: a critical review. Nutr. Res. Rev. 9, 89–110.

Kramer MS, Chalmers B, Hodnett ED, Sevkovskaya Z, Dzikovich I, Shapiro S, Collet JP, Vanilovich I, Mezen I, Ducruet T, Shishko G, Zubovich V, Mknuik D, Gluchanina E, Dombrovskiy V, Ustinovitch A, Kot T, Bogdanovich N, Ovchinikova L & Helsing E (2001): Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT): a randomized trial in the Republic of Belarus. JAMA 285, 413–420.

Labbok MH (1999): Health sequelae of breastfeeding for the mother. Clin. Perinatol. 26, 491–503.

Labbok MH, Perez-Escamilla R, Peterson AE & Coly S (1997): Breastfeeding and Child Spacing Country Profiles. Washington, DC: Institute for Reproductive Health.

LINKAGES (1998): Facts for Feeding: Guidelines for Appropriate Complementary Feeding of Breastfed Children 6–24 Months of Age. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development.

LINKAGES (1999): Facts for Feeding: Recommended practices to improve infant nutrition during the first six months. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development.

Ludvigsson JF (2003): Breastfeeding intentions, patterns, and determinants in infants visiting hospitals in La Paz, Bolivia. BMC Pediatr. 3, 5.

Martin RM, Smith GD, Mangtani P, Frankel S & Gunnell D (2002): Association between breastfeeding and growth: the Boyd-Orr cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 87, F193–F201.

Pérez-Escamilla R (1997): Infant feeding and lactational amenorrhea in developing countries: Results from DHS II & DHS III. Washington, DC: Institute for Reproductive Health.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Lutter C, Segall AM, Rivera A, Trevino-Siller S & Sanghvi T (1995): Exclusive breast-feeding duration is associated with attitudinal, socioeconomic and biocultural determinants in three Latin American countries. J. Nutr. 125, 2972–2984.

Pérez-Escamilla R, Segura-Millan S, Canahuati J & Allen H (1996): Prelacteal feeds are negatively associated with breast-feeding outcomes in Honduras. J. Nutr. 126, 2765–2773.

Popkin BM, Adair L, Akin JS, Black R, Briscoe MS & Flieger W (1990): Breastfeeding and diarrheal morbidity. Pediatrics 86, 874–882.

Raisler J, Alexander C & O’Campo P (1999): Breastfeeding and infant illness: a dose–response relationship. Am. J. Public Health 89, 25–30.

Scott JA, Landers MCG, Hughes RM & Binns CW (2001): Factors associated with breastfeeding at discharge and duration of breastfeeding. J. Paediatr. Child Health 37, 254–261.

Simondon K & Simondon F (1997): Age of introduction of complementary food and physical growth from 2 to 9 months in rural Senegal. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 51, 703–707.

Valdes V, Pugin E, Schooley J, Catalan S & Aravena R (2000): Clinical support can make the difference in exclusive breastfeeding success among working women. J. Trop. Pediatr. 46, 149–154.

Victora CG, Fuchs SC, Flores JA, Fonseca W & Kirkwood B (1994): Risk factors for pneumonia among children in a Brazilian metropolitan area. Pediatrics 93, 977–985.

Whaley SE, Meehan K, Lange L, Slusser W & Jenks E (2002): Predictors of breastfeeding duration for employees of the Special Supplemantatal Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 102, 1290–1293.

WHO (2001): Collaborative study team on the role of breastfeeding on the prevention of infant mortality. Effect of breastfeeding on infant and child mortality due to infectious diseases in less developed countries: a pooled analysis. Lancet 355, 451–455.

WHO (2002): The Optimal Duration of Exclusive Breastfeeding a Systematic Review. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Contributors: BAA was responsible for all aspects of study coordination, protocol development, staff training and report writing. She also participated in proposal writing, obtaining supplemental funds, recruiting, data collection and analysis. RP-E was responsible for proposal writing and obtaining funds for the project. He was involved in protocol development, content validity assessment, data analysis and report writing. AL provided collaboration from the University of Ghana, obtained permission from the health institutions used and was also involved in content analysis, study coordination and report writing. JA was involved with selection of MCH clinics, study coordination, recruitment, data collection, entry and cleaning.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aidam, B., Pérez-Escamilla, R., Lartey, A. et al. Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in Accra, Ghana. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 789–796 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602144

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602144

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Ghana

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

The effect of educational support intervention including peer groups for infant care on the growth rates of infants, breastfeeding self-efficacy and quality of life of their mothers in Iran: study protocol

Reproductive Health (2022)

-

Inequalities in Access and Utilization of Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Services in sub-Saharan Africa: A Special Focus on Urban Settings

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2022)

-

Prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding among rural mothers of infants less than six months of age in Southern Nations, Nationalities, Peoples (SNNP) and Tigray regions, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study

International Breastfeeding Journal (2020)

-

Estimating the rate and determinants of exclusive breastfeeding practices among rural mothers in Southern Ghana

International Breastfeeding Journal (2020)