Abstract

Background

Medical male circumcision (MMC) is now considered one of the best available evidence-based biomedical HIV prevention interventions. However, there is some concern about risks for behavioural disinhibition, or risk compensation, following MMC.

Purpose

The aim of this study was to test a brief one-session (180 min) group culturally tailored HIV risk reduction counselling intervention among men undergoing medical circumcision in South Africa in order to limit behavioural disinhibition.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial design was employed using a sample of 150 men, 75 in the experimental group and 75 in the control group. Comparisons between baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments on several key behavioural outcomes addressed by the intervention were done.

Results

Our study found that behavioural intentions and risk reduction skills significantly increased and sexual risk behaviour (reduction of the number of sexual partners and the number of unprotected vaginal sexual intercourse occasions) significantly decreased in the experimental compared to the control condition. However, male role norms did not change among the intervention conditions over time, while AIDS-related stigma beliefs significantly reduced in both conditions over time.

Conclusion

Study findings show that a relatively brief (one session) and focused HIV risk reduction counselling can have at least short-term effects on reducing sexual risk behaviours in populations at high risk for behavioural disinhibition following medical male circumcision.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Southern Africa is home to two thirds of the more than 33 million people living with HIV/AIDS in the world. Although only 10% of the world’s population live in sub-Saharan Africa, more than 85% of the world’s AIDS-related deaths have occurred in this region [1]. The Republic of South Africa’s HIV/AIDS epidemic has only recently matured, and yet, 11% of South Africans are infected with HIV [2, 3]. Recently, three rigorous randomized clinical trials demonstrated approximately 60% reductions in HIV transmission rates following medically performed male circumcision surgery in South Africa, Uganda, and Kenya [4–6]. Consequently, international organisations under the global leadership of both World Health Organization (WHO) and UNAIDS have recommended male circumcision in sub-Saharan African countries including in South Africa as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention package among males [7, 8]. Although the protective value of medical male circumcision (MMC) for HIV prevention is now indisputable, there is evidence that the protective benefits of MMC are undermined by HIV-related sexual risk practices, including reductions in use of condoms and increases in numbers of sex partners. Early epidemiologic studies suggested that circumcised men engage in higher risk behaviours, and the results of two of the three RCTs demonstrate evidence for increases in risk practices following MMC [4, 6]. Although substantial concerns have been raised about the risks for behavioural disinhibition, or risk compensation, following MMC, we are not aware of any theory-based behavioural interventions designed to reduce behavioural disinhibition.

This study is in response to the urgent need for behavioural disinhibition prevention interventions for men who undergo MMC in Southern Africa. Brief theory-based behavioural risk reduction counselling for men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection (STI) services in South Africa have shown to be effective. Our current multi-clinic randomized controlled trial (RCT) is testing a 180-min behavioural risk reduction counselling intervention that is grounded in the Information–Motivation–Behavioural Skills (IMB) Model [9]. A similar risk-reduction counselling model has shown promising effects in two previous smaller-scale RCTs [10, 11]. A full description of how the original intervention was adapted to an HIV behavioural disinhibition risk reduction intervention for recently circumcised South African men is described by Peltzer et al. [9]. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of a one-session (180 min) group HIV risk reduction counselling intervention trial with 150 men undergoing medical male circumcision in South Africa.

Methods

Study Design and Procedures

This study used an experimental design where male patients booked for circumcision in three hospitals in Mpumalanga province in South Africa were selected and randomly assigned to receive either the experimental HIV intervention or the comparison condition. The medical provider in the hospital setting “referred”, after physical fitness examination and pre-operation counselling for circumcision, individuals 18 years and above prior to the theatre date to a group intervention session at the hospital. Following informed consent and completion of baseline assessment prior to circumcision, the enrolment coordinator drew a random computer-generated group assignment in a sealed envelope to determine each participant’s intervention condition: (1) a 180-min motivational skills building experimental condition and (2) a 60-min health improvement education comparison condition that included a brief segment on HIV prevention education information. Random assignment occurred following the baseline assessment to assure that recruitment and assessment staff remained blinded to condition assignments as well as at follow-up assessments. Both conditions were conducted the day prior to circumcision; the two conditions maintained a follow-up assessment at 3 months. For both conditions, the programmes were delivered in small groups consisting of 8 to 12 men per group. A total of 15 groups were conducted.

The sample included 150 men, 75 in the experimental and 75 in the comparison group. The mean age in the experimental group was 20.8 years (SD = 2.0) and in the comparison group, 21.9 years (SD = 2.6), t (1) = 2.84, p = 0.005; range, 18–28 years. The number of men who had had sex with a woman in the past 3 months in the experimental group was 42 (56.0%) and in the comparison group, 54 (72%) (χ 2 [df = 1] = 4.17, p = 0.041). There were no significant differences of other demographic variables (number of formal education completed in the experimental group, 7.7 years (SD = 0.8) and in the comparison group, 7.0 years (SD = 0.8), as well as employment and marital status).

Participants were scheduled for follow-up assessments 3 months after counselling. They received 100 South African Rand (approximately US $12 at the time of the study) to compensate for completing the baseline and returning to the clinic for the follow-up assessment. Following the 3-month follow-up, participants in the health education control condition were offered the experimental HIV risk reduction intervention. All study procedures were approved by the Human Sciences Research Council Research Ethics Committee and the Mpumalanga Provincial Department of Health in South Africa as well as the Institutional Review Board of the University of Connecticut.

Intervention

The intervention was similar to that used in our earlier studies [10, 11] except that male circumcision disinhibition content was added and that the duration of the experimental condition was extended from 60 min to 180 min, while that for the comparison condition was increased from 20 min to 60 min. This was done in order to allow for adequate time to complete the group counselling session. The intervention emphasized sexual transmission risk reduction through skills building and personal goal setting. The intervention activities were also geared toward addressing gender roles, particularly exploring meanings of masculinity and reducing adversarial attitudes toward women. Participants identified high-risk sexual behaviours (triggers) leading to problem solving skills as applied to identifying and recognizing risk. These same concepts were applied to identifying and problem-solving antecedents to violent reactions toward women. Condom use skills were trained through interactive group activities, and sexual communication skills were rehearsed in response to sexual risk scenarios for skills training.

Participants provided feedback to each other in behavioural rehearsal enactments and worked toward setting goals for HIV risk reduction.

Alcohol use was integrated within the motivational component by adapting the WHO’s brief alcohol intervention model as was done by Kalichman et al. [10]. Alcohol use in sexual contexts was specifically discussed in relation to risk situations. The final component of the workshop focused on behavioural self-management and sexual communication skills building exercises [9].

Group Facilitator Training and Intervention Quality

The group facilitators for both conditions consisted of one man and one woman with prior experience in conducting HIV/AIDS education programmes. To protect against facilitator drift, the interventions were completely manualized, and poster-size flipcharts were used to guide the groups through the session content. The facilitators attended weekly supervision meetings with the project manager to discuss their groups and adherence to the protocol.

Measures

All measures were administered at the baseline, and 3-month follow-up assessments were in Ndebele, the language spoken by nearly all clinic patients. Measures included descriptive information (demographics, substance use, and HIV risk history), IMB constructs, and sexual behaviour.

Information

HIV/AIDS Knowledge

A 14-item test was used to assess AIDS knowledge. Items were adapted from a measure reported by Carey and Schroder [12] and reflected information about HIV transmission, condom use, and AIDS-related knowledge and were responded to Yes, No, or Don’t Know. The HIV/AIDS knowledge test was scored for the number of correct responses, with Don’t Know responses scored vs. incorrect, and the possible range of scores 0 to 14 expressed as the percentage correct. The HIV/AIDS knowledge test demonstrated heterogeneous item content as is expected of knowledge tests; Cronbach’s alpha (α), a coefficient of reliability, was .64 and .78 at pre- and posttest, respectively, for this study sample.

Motivation

Behavioural Intentions

Participants responded to a nine-item scale assessing personal intentions to engage in risk-reducing behaviours. Examples of items include “I will tell my partner that we need to use a condom” and “I will not drink alcohol before sex” and were anchored on four-point scales ranging from 1 = I will not do, to 4 = I will do. Theories of behaviour change postulate a close temporal relationship between intentions to change behaviour and changes in actual behaviour [13]. Fisher and Fisher [14] suggest the use of behaviour intention items to assess motivation to change within the IMB framework; α = .90 and α = .94 at pre- and posttest, respectively, for this sample.

Behavioural Skills

Risk Reduction Skills Self-efficacy

Based on social cognitive theory, our measure allows participants to judge their capability across domain-relevant activities and levels of situational demands. Also, as recommended, our measure is tailored to the relevant domains, and the scenarios reflect information gained from our target population. Using information from formative research, we generated six scenarios within which potential risks are realistic and personally relevant to men in South Africa (e.g. “I am confident that I can suggest using condoms with new sex partners.”), with responses on a four-point scale, 1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree, α = .87 and α = .94 at pre- and posttest, respectively.

Risk Behaviours and Risk Reduction Behaviours

Unprotected and Protected Sexual Behaviors

Participants were asked to report the number of times in the past 1 month and again in the past 3 months that they engaged in sexual intercourse (vaginal, anal) and the number of times of protected sexual intercourse. Using 1-month and 3-month time frames allows for baseline data that both precedes and follows surgery. All response formats were open-ended, requiring numerical values for responses to avoid subtle influences on response sets that can result from closed formats [15, 16].

Strategies for Risk Behaviour Change

Participants were asked to report their use of 13 behavioural strategies to reduce their risk for HIV and other STIs [17]. Examples of items include “I discussed using condoms with a sex partner”, “I made sure that I had condoms with me every time I had sex”, and “I avoided using alcohol and other drugs before sex” responded in “Yes” or “No” for each strategy practised in the past 1.5 month, α = .86 and α = .91 at pre- and posttest, respectively, for this sample.

Potential Moderators

Alcohol Use

Alcohol use was assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). The AUDIT is a measure of the prevalence of alcohol use [18]. Cronbach’s alpha for the AUDIT was .91 at baseline and .92 at follow-up for this sample.

Male Role Norms

Participants completed the ten-item Male Role Norms Scale [19] to assess acceptance of traditional masculinity and masculine social roles. The Male Role Norms Scale has three underlying dimensions: status norms “It is essential for a guy to get respect from others”, toughness norms “A young man should be physically tough, even if he’s not big”, and anti-femininity norms “I don’t think a husband should have to do housework”. The eight-item version of the scale has shown excellent psychometric characteristics [19, 20], α = .76 and α = .93 at pre- and posttest, respectively, for this sample.

AIDS-Related Stigma Beliefs

We administered nine AIDS-related stigma items that have been adapted from previous research for use in South Africa [21]. The AIDS stigma items reflect negative beliefs about people living with AIDS (e.g. dirty, cursed, untrustworthy), shamefulness of the behaviour of people living with HIV/AIDS (e.g. guilt, shame, weak), and endorsement of social sanctions against people with HIV/AIDS (e.g. should not work with children, restrictions on freedom). The items are responded to on a strongly agree = 4 to strongly disagree = 1 scale, and were internally consistent, α = .82 and α = .88 at pre- and posttest, respectively, for this sample.

Data Analyses

Variables that were significantly skewed, particularly levels of sexual behaviours, were transformed using the formula log10 (x + 1) with non-transformed observed values presented in the tables. These data served as the dependent variable and were analysed by means of a 2 × 2 repeated measures analysis of variance, with Time (pre–post intervention) being the within factor and Group (experimental comparison) being the between factor. Missing data due to non-response were deleted on an analysis-by-analysis basis. We used an intent-to-treat analysis by including all participants who completed baseline assessments and were randomized to intervention conditions. Individual cell sizes vary due to missing values. Statistical significance was defined using the conventional value of p < 0.05.

Results

Retention and Attrition of Participants

A total of 150 men enrolled in the study, completed baseline assessments, and were randomized to two conditions. All men completed one group session, with 146 (97.3%) completing the 3-month follow-up; of the four men who could not be followed up, all could not be located. There was a 5.3% (4/n) attrition in the comparison group and 0% in the motivational skills building group.

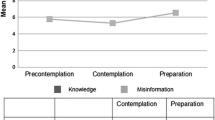

Information and Motivation Outcomes

Analysis of variance between intervention conditions on the HIV/AIDS knowledge test scores at pre- and post-intervention showed no differences at follow-up. Behavioural intentions, risk reduction skills self-efficacy, and behavioural skill enactments significantly increased in the intervention compared to the comparison group at follow-up. Male role norms did not change among the intervention conditions over time, and AIDS-related stigma beliefs reduced in both conditions over time (see Table 1).

Sexual and Other Risk Behaviours

Analyses found a significant reduction of the number of sexual partners and the number of unprotected vaginal sexual intercourse occasions between experimental and control conditions at 3-month follow-up (see Table 2).

Discussion

The current study is the first, to our knowledge, to test a brief theory-based behavioural HIV risk reduction counselling intervention performed in the context of medical male circumcision. Our study used a randomized design to test the potential efficacy of a culturally tailored risk reduction counselling intervention for use in the context of medical circumcision in South Africa. Positive results of this 180-min risk reduction counselling intervention are consistent with other studies showing that a relatively brief (one session) and focused HIV risk reduction counselling can have at least short-term effects on reducing sexual risk behaviours in populations at high risk for behavioural disinhibition following medical male circumcision.

The lack of change in HIV/AIDS risk-related knowledge and in male role norms in the present study is very interesting. With regard to the former, this could show the results of a ceiling effect as HIV/AIDS knowledge is generally high in South Africa [2, 3, 22]. As for male role norms, it suggests that these South African men studied are very resistant to change due to sociocultural values and norms dictating how men should behave being strongly entrenched in the communities in which the participants live. Similar resistance has also been noted with another intervention addressing gender-based violence and HIV risk reduction which our research team developed [23, 24]. There is therefore a need for a multi-level intervention with the brief theory-based behavioural HIV risk reduction counselling intervention which was developed and evaluated in this study targeting men who have undergone MMC, while another intervention would target both men and women at the community level to reinforce what the men learned in their men-only counselling groups. There is an urgent need for a larger randomized controlled trial to be conducted followed by operational research as MMC is being rolled out.

Study limitations include the intervention in the current research was tested in a trial with a small sample size. In addition, the current study represented an initial efficacy test of an adapted counselling model to male circumcision and therefore only had a short follow-up period. Finally, our initial test of intervention efficacy relied on self-report measures of sexual risk and alcohol use behaviours.

References

UNAIDS. UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2010.

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Parker W, Bhana A, Zuma K, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2005. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2005. p. 2005.

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-van-Wyk V, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence, behaviour and communication survey 2008: a turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009.

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, et al. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298.

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66.

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56.

World Health Organisation (WHO). Information package on male circumcision and HIV prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

World Health Organisation (WHO). New data on male circumcision and HIV prevention: policy and programme implications. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Peltzer K, Kekana Q, Banyini M, Jooste S, Simbayi L. Adaptation of an HIV behavioural disinhibition risk reduction intervention for recently circumcised South African men. Gender and Behaviour 2011 (in press)

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, Peltzer K. HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(5):594–600.

Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, Jooste S, Cain D, Cherry C, et al. Theory-based HIV risk reduction counselling for sexually transmitted infection patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(12):727–33.

Carey MP, Schroder KE. Development and psychometric evaluation of the brief HIV knowledge questionnaire (HIV-KQ-18). AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:174–84.

Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1980.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:455–74.

Weinhardt LS, Forsyth AD, Carey MP, Jaworski BC, Durant LE. Reliability and validity of self-report measures of HIV-related sexual behavior: progress since 1990 and recommendations for research and practice. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27(2):155–80.

Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: I. Item content, scaling, and data analytical options. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):76–103.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M, DiFonzo K, Simpson D, Austin J, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce HIV transmission risks in HIV-positive people. Am J Prev Med. 2001;21(2):84–92.

Babor TF, Higgens-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Guidelines for use in primary care. World Health Organization, Geneva, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence. WHO/MSD/MSB/01.6a, 2001.

Thompson EH, Pleck JH, Ferrera DL. Men and masculinities: scales for masculinity ideology and masculinity-related constructs. Sex Roles. 1992;27:573–607.

Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL, Ku LC. Masculinity ideology: its impact on adolescent males’ heterosexual relationships. J Social Issues. 1993;49:11–29.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):442–7.

Shisana O, Simbayi L. Nelson Mandela/HSRC Study of HIV/AIDS: South African national HIV prevalence, behavioural risks and mass media household survey 2002. Cape Town: Human Sciences Research Council Press; 2002.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Cherry C, Strebel A, Kalichman MO, et al. HIV/AIDS risk reduction and domestic violence prevention intervention for South African men. Int J Mens Health. 2008;7(3):255–73.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Clayford M, Arnolds W, Mxoli M, et al. Integrated gender-based violence and HIV risk reduction intervention for South African men: results of a quasi-experimental field trial. Prev Science. 2009;10(3):260–9.

Acknowledgements

National Institute of Mental Health Grant R03 MH082674-01 supported this research.

Competing Interests

None declared

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peltzer, K., Simbayi, L., Banyini, M. et al. HIV Risk Reduction Intervention Among Medically Circumcised Young Men in South Africa: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int.J. Behav. Med. 19, 336–341 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9171-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-011-9171-8