Abstract

Background

Cultural competency training has been proposed as a way to improve patient outcomes. There is a need for evidence showing that these interventions reduce health disparities.

Objective

The objective was to conduct a systematic review addressing the effects of cultural competency training on patient-centered outcomes; assess quality of studies and strength of effect; and propose a framework for future research.

Design

The authors performed electronic searches in the MEDLINE/PubMed, ERIC, PsycINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science databases for original articles published in English between 1990 and 2010, and a bibliographic hand search. Studies that reported cultural competence educational interventions for health professionals and measured impact on patients and/or health care utilization as primary or secondary outcomes were included.

Measurements

Four authors independently rated studies for quality using validated criteria and assessed the training effect on patient outcomes. Due to study heterogeneity, data were not pooled; instead, qualitative synthesis and analysis were conducted.

Results

Seven studies met inclusion criteria. Three involved physicians, two involved mental health professionals and two involved multiple health professionals and students. Two were quasi-randomized, two were cluster randomized, and three were pre/post field studies. Study quality was low to moderate with none of high quality; most studies did not adequately control for potentially confounding variables. Effect size ranged from no effect to moderately beneficial (unable to assess in two studies). Three studies reported positive (beneficial) effects; none demonstrated a negative (harmful) effect.

Conclusion

There is limited research showing a positive relationship between cultural competency training and improved patient outcomes, but there remains a paucity of high quality research. Future work should address challenges limiting quality. We propose an algorithm to guide educators in designing and evaluating curricula, to rigorously demonstrate the impact on patient outcomes and health disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

BACKGROUND

In 2002 the Institute of Medicine released Unequal Treatment 1, a seminal report documenting extensive evidence of disparities in the burden of disease, quality and appropriateness of care, and health outcomes among specific US populations, in particular ethnic minorities. Multiple, interdependent factors have been shown to contribute to health disparities, including patient, clinician, health system and environmental variables2, 3. In response to calls to address diverse health care needs of the US population, curricular tools have been developed with the intention of improving clinician and patient communication and behaviors to reduce these disparities4–7. There is an implicit understanding that providing culturally effective care will lead to improved quality of care1,8–11. But there remains a need for evidence that links carefully developed curricula with patient-centered and clinical outcomes6,10–12.

In a systematic review examining the effectiveness of cultural competence (CC) curricula13, Beach and colleagues found 52 studies addressing impact on provider competencies but only 3 addressing patient outcomes; they concluded that evidence that CC training improves patient adherence and health care equity was lacking. CC training reviews have focused on the effect of training on learners’ acquisition of skills, knowledge and attitudes13, and the rigor of the methods and assessments of curricular dissemination and replication10,14,15. Two reviews addressed training effect on health care systems and mental health services16,17; both concluded that the evidence for effectiveness of training on service delivery and health status was limited. The recent randomized controlled trial by Sequist and colleagues18 reporting that CC training and performance feedback did not improve documented disparities in diabetes care outcomes between black and white patients has prompted a reexamination of the impact of CC curricula on patient outcomes.

OBJECTIVES

Since the Beach 200513 review, a variety of valid measures to examine the quality of research studies have emerged19–23. Our goal was to reevaluate and update the literature since the Beach review, assess the quality of studies and overall impact of training on patient outcomes, and propose a framework for future research. Our questions were: What is the evidence for a direct link between provider CC training and patient outcomes (number and type of studies)? Are existing studies well designed and adequately powered to examine patient outcomes (quality of studies)? Is there robust evidence for a lack of association between provider training and patient outcomes?

Based on our review and previously described theoretical models, we propose an algorithm for conducting studies on educational interventions that specifically examine patient outcomes as primary endpoints.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

We conducted a systematic literature review to assess studies with any CC intervention for health care providers or learners where impact on patients and/or health care utilization was measured. We used formal methods for literature search, selection, quality assessment and synthesis, and followed accepted guidelines24,25. Between February and March 2010, we conducted an electronic search of the MEDLINE/PubMed, PsycINFO, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Web of Science databases for articles in English published between January 1990 and March 2010. Using MEDLINE/PubMed, we developed an initial search template (below) and applied it to the databases to maximize sensitivityFootnote 1:

(cultural competence OR cultural competency OR cultural diversity OR cultural diversities OR health disparities OR health disparity) AND (training OR curriculum OR teaching) AND (patient outcomes OR outcome assessment OR health care quality assurance) AND (professional patient relations OR patient compliance OR patient adherence OR patient satisfaction OR patient cooperation).

In addition we searched the Cochrane database of systematic reviews26, the BEME resource for evidence-based education studies and systematic reviews27, and an educational research clearinghouse28. We also searched the bibliographies of key review articles12–17, and contacted authors and queried experts in the field for additional studies that may have been missed.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

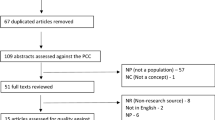

Articles were selected from abstract lists generated by the electronic and hand searches, based on pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Eligible studies had to (1) represent original studies with learners/providers and patients; (2) include provider/learner cultural competency education/training; and (3) measure specified patient-centered outcomes (such as satisfaction) or disease outcomes (such as blood pressure), and/or health care utilization or processes of care. Studies with multiple interventions such as provider and patient education, or that had systems interventions (such as telephone reminders) were eligible. We excluded articles that were not in English; did not have original provider/learner/patient data; contained curricula with patient but not provider education; or that described only generic communication skills curricula. Reviews, editorials and unpublished abstracts and conference proceedings were excluded.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Three authors (DAL, ELR and AG) reviewed all abstracts from the database searches and retrieved full-text articles for further review. Each abstract list was independently reviewed by two authors. Then four authors (DAL, ELR, AG, SB) read the retrieved articles for final article selection and quality assessment. The bibliographies of the retrieved full-text articles were hand-searched. Finally we contacted authors for additional information if indicated. We divided the articles so that two reviewers were assigned to each full-text article for independent quality assessment. To rate the studies for quality, we considered several criteria19–23. We chose and adapted the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology: Explanation and Elaboration) criteria for convenience and scope of scoring19,29,30. Items 4 to 21 from the STROBE checklist30 included assessment of study design, setting, participants, confounding variables, bias, study size, statistical analysis, outcome measures, results, limitations and study generalizability as key constructs. Using scores of 0 (not done), 1 (done partially) and 2 (done well) with scores doubled for statistical methods and outcomes, our scheme (see Appendix) produced a score range of 0 (lowest) to 40 (highest quality). We also used the MERSQI (Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument), a validated ten-item tool designed for medical educational interventions with a score range of 5 (lowest) to 18 (highest) as a second measure20. The MERSQI utilized similar constructs of study design, sampling, validity, data analysis and outcomes to assess research quality. Data abstraction was standardized and rating reliability optimized by discussion to achieve rater agreement for the individual scale items, before independent rating. We designated studies as being of low, moderate and high quality using tertiles of scores for the STROBE and MERSQI. If the two primary reviewers of an article independently placed the article into different categories (tertiles) for quality, the remaining two (secondary) reviewers also independently scored the article. Consensus was then derived by a joint decision of all four reviewers.

Each primary reviewer pair assessed the effect size of curricular interventions on patient-centered outcomes, as – (negative/causing harm), 0 (no effect), + (small), ++ (moderate) or +++ (high benefit) by interpreting the magnitude of meaningful clinical and/or patient-reported benefit or harm as reported in each study, by discussion and consensus, with adjudication and input from the other two reviewers as needed.

RESULTS

Search Results and Data Abstraction

The electronic search yielded 251 abstracts from the MEDLINE/PubMed, 96 from the PsycINFO, 275 from the CINAHL, 24 from the ERIC and 98 from the Web of Science databases (Fig. 1). A total of 15 abstracts were selected. All reviewers agreed on the abstraction of articles for full review. Six abstracts from MEDLINE/PubMed, four from PsycINFO, four from CINAHL, none from ERIC and one from Web of Science were identified for full-text review. Three of the abstracts were duplicated in 4 of the 5 databases, with the result that 12 articles were retrieved for full-text review. Subsequent bibliographic review of these and the previously conducted reviews10,12–17 yielded another 5 articles for a total of 17 articles representing 17 different studies. Of the 17 articles that underwent full-text review, 10 were excluded from further quality assessment because of (1) having no curricular intervention (n = 5), (2) having no patient or health care utilization outcomes (n = 4), and (3) being interim reports with results pending (n = 2), leaving 7 studies in the final quality analysis16,29–34. Among the seven studies, quality rating discrepancies occurred in two studies using STROBE and two using MERSQI, with final rating achieved by adjudication involving secondary reviewers.

Qualitative Synthesis of Selected Studies

Clinical or patient-based endpoints were at least one of the outcomes of interest in all seven studies. Three studies involved physicians, two involved multiple health professionals and students (nurses, home health care, community health workers and ‘allied health’) and two involved mental health professionals. Two were quasi-randomized, two were cluster randomized, and three were pre/post field studies. The number of learners/providers in each study ranged from 8 to over 3,700 and number of patients from 37 to 7,557. The curricular interventions were varied in content, theory and method (not described in one study). Examples of content include the Pederson’s triad of cross-cultural counseling and a language/culture immersion course. Duration of curricular exposure ranged from 4 h to 10 weeks (Table 1). No study examined the dose-response association between training and patient outcomes, or differential effects of training among different health professionals on patient outcomes. The patient outcomes assessed included patient or family satisfaction, patient self-efficacy, clinical outcomes (blood pressure, weight change and HbA1c) and patient assessment of provider cultural competency (Table 2). Mean study quality scores ranged from 8 to 26 for the STROBE and 5.5 to 12.0 for the MERSQI. Quality of studies was rated as moderate (n = 4) to low (n = 3), with none of high quality. The two tools categorized all seven studies in similar tertiles for quality. Effect size ranged from 0 to ++ (unable to assess in two studies) with no study that reported a harmful (-) or highly beneficial (+++) effect (Table 2). The three studies reporting a positive effect were free of “spin” in their interpretation of positive findings31. Study variability for providers/learners, patients, methods and outcomes prevented aggregate quantitative assessment and the use of sensitivity analyses to test for heterogeneity24,32, and pooling of data for effect size. Hence, a qualitative synthesis and analysis are presented.

Wade 199133

This (quasi)-randomized controlled trial measured the effect of 4 h of cultural sensitivity training on a convenience sample of eight Master's level psychology female counselors and their black female patients in a college counseling center. Patients reported a significant positive effect on counseling skills and cultural sensitivity for the intervention compared with control counselors. Small provider sample, self-selection, patient attrition and unique setting limited interpretation, generalizability of the findings and study quality (rating: low).

Mazor 200234

This pre/-post field study examined a Spanish language proficiency class for faculty non-fluent in Spanish. Satisfaction ratings of 143 families, administered in Spanish, showed significant improvement for ‘physician concern’ (OR 2.1), ‘feeling comfortable with physician’ (OR 2.6), ‘physician being respectful’ (OR 3.0) and ‘physician listened to family’ (OR 2.9). High response rate, valid measures and curricular specificity contributed to the study’s quality (rating: moderate).

Way 200235

This pre/post analysis of inpatient perceptions of mental health staff and the environment in psychiatric units was conducted before and after a mandated statewide core curriculum consisting of six modules that included CC in one module. The curriculum was delivered to over 3,700 hospital staff and providers at 20 hospitals over 2 years. At three hospitals, 77 patients perceived greater ‘environmental changes favoring their interests’ and ‘receptiveness toward the staff.’ Effect of the CC training could not be assessed because of inconsistent data and small patient numbers in proportion to providers trained, both factors contributing to low study quality (rating: low).

Majumdar 200436

This (quasi)-randomized study examined 36 h of cultural sensitivity training vs. no training on providers and their patients. Longitudinal use of six validated scales assessing patient satisfaction, resourcefulness, access to services, mental and physical health at 3 to 18-months contributed to study quality. A positive effect was seen for patient use of social and economic resources. However, high attrition among patients (from 133 at baseline to 37) and providers (from 114 to 76) limited validity (rating: moderate).

Thom 200637

This cluster randomized trial randomized primary care physicians from two sites (n = 23) to a half-day or a three-session curriculum with feedback vs. physicians from two sites (n = 30) to feedback only. Patient reports of their physician’s cultural competency comprised the feedback and the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were patient satisfaction, patient trust and clinical outcomes of blood pressure, HbA1c and weight loss at 6 months. Two hundred forty-seven patients rated the ‘training + feedback’ and 182 rated the ‘feedback only’ group. No significant differences were found. Study quality was enhanced by adequate patient sampling and use of valid outcome measures (rating: moderate).

McElmurry 200938

This 3-year pre/post multisite field study of 386 clinic-based providers and students included Spanish immersion or language classes and cultural workshops as interventions to increase competency to care for 1,994 Limited English Proficiency diabetic patients. A second intervention consisted of community health workers (CHW) added as a systems change component. Patient outcomes were assessed only for the CHW intervention. For the subset of patients with at least two visits with CHW (n = 392), the study demonstrated reduced patient no-show rates and improvements in diabetes self-monitoring, and HbA1c. However, the impact of the CC curriculum was assessed only by provider/student ratings and language skills. Therefore, the effect on patient outcomes could not be independently assessed, limiting study quality (rating: low).

Sequist 201018

This 12-month cluster randomized, controlled trial evaluated the effect of CC training and clinical performance feedback for 15 (education plus feedback) compared with 16 (feedback only) primary care teams. The 31 teams consisted of 91 physicians and 33 nurse practitioners or physician assistants at eight ambulatory centers. Race-stratified physician-level diabetes performance reports with recommendations were provided at 4 and 9 months. Eighty-two percent of clinicians were white. No significant differences in the primary outcome of disparity reduction for black vs. white patients were found. Study quality was enhanced by a low provider dropout rate (15%), high patient numbers (7,557) and use of valid measures, but subgroup analyses were missing (rating: moderate).

DISCUSSION

We believe this is the first systematic review to critically assess the quality of studies that determine whether educational interventions to improve the cultural competence of health professionals are associated with improved patient outcomes. This paper updates the 2005 findings of Beach et. al.13 in examining new curricular offerings (adding four new studies) and provides an analysis of research quality. As is the case with many educational studies20,24, researchers faced threats to external validity. Importantly, the majority of the studies did not provide sufficient information on the curricula, provider/learners or patients to allow replication. Many studies lacked descriptions of potential variables that may have impacted results. Related to the provider, these include their prior training, age, ethnicity, gender, baseline attitudes and skills, and motivation to participate in training. Patient factors were not adequately accounted for a priori. Provider and patient race and language concordance and their potential effects were not consistently reported. Generalizability of findings was limited as study communities, and settings were often unique. Moreover, some studies had multiple objectives with cross-contamination affecting patient outcomes, making it difficult to isolate the effect of provider training from system changes. The studies, albeit of limited quality, reveal a trend in the direction of a positive impact on patient outcomes. However, overall the current evidence appears to be neither robust nor consistent enough to derive clear guidelines for CC training to generate the greatest patient impact. It is also possible that CC training as a standalone strategy is inadequate to improve patient outcomes and that concurrent systemic and systems changes, such as those directed at reducing errors or improving practice efficiency, and the inclusion of interpreters and community health promoters as part of the health care team, are needed to optimize its impact.

Our review used a comprehensive search strategy and a systematic process to assess study quality and identify potential reasons for inconsistent results. However, we were challenged to find an ideally designed tool for quality assessment. By using both the STROBE criteria (29-30, Appendix) and the MERSQI20, we strove to maximize the validity of the quality review.

Synthesizing existing conceptual models of cultural competence with an established framework for evaluating methodological rigor in education research, we propose an algorithm (Fig. 2) as a guide to achieving excellence in methodological design. This model addresses both experimental (randomized, cluster or quasi-randomized) and field (pre/post case control or cohort, or cross-sectional) designs. The algorithm is based first on the theoretical framework described by Cooper and colleagues39 in which the quality of providers including their cultural competence is one of four mediators (the other three being appropriateness of care, efficacy of treatment and patient adherence) of high quality patient outcomes (categorized as health status, service equity and patient views of care). They stated that ‘… important limitations of previous studies include the lack of control groups, nonrandom assignment of subjects to experimental interventions, and use of health outcome measures that are not validated. Interventions might be improved by targeting high-risk populations, focusing on quality of care and health outcomes’39. Second, we built on the model of methodological excellence advocated by Reed et al.20, who noted that existing educational studies of the highest quality used randomized controlled designs, had high response rates and utilized objective data, valid instruments and statistical methods that included appropriate subgroup analyses, with accountability for confounding variables.

We recommend that educators consider Figure 2 a realistic guiding roadmap. When designing the conceptual framework of proposed studies, we advocate that researchers consider the strength of the existing evidence linking cause and effect40 to perform sample size calculations, as well as the reproducibility and generalizability of the results (internal and external validity, respectively). We propose that the description of providers/learners include information on past training, demographics, cultural and linguistic background, baseline skills and attitudes and the health system (context) within which they function. Patients should be characterized by medical condition, demographics, health literacy, language proficiency, health beliefs, socioeconomic background and other potential confounders. The curriculum implemented should be sufficiently well described for replication, to include core resources and teachers. The cost of training should be made explicit. Study designs should consider the type of subsequent analyses testing the relationship between the intervention and patient outcomes29,39. Provider educational interventions are often distant from clinical outcomes, and subjective constructs such as patient trust and the quality of the patient experience using validated measures41 have emerged as outcomes of intrinsic value that should also be considered in the cause-effect dynamic. As well as traditional objective clinical indicators, outcomes should include process measures of the patient-physician partnership42,43, which may be considered intermediate or standalone goals in the attainment of best health care quality. All reasonable confounders should be captured to rule out alternative hypotheses and increase confidence in the results. Heterogeneity of providers and patients should be accounted for by subgroup analyses when reporting results as CC training may have differential effects on different patients by ethnicity or disease. The durability of training on patient outcomes should be tested. Where system interventions other than provider training are concurrently introduced, three separate study arms may be needed to isolate the effect of training from the system change. As our systematic review revealed, these standards have not been adequately met. However, two registered trials currently underway (results pending) appear to meet many of the suggested criteria for experimental design, and results are eagerly awaited44,45, personal communication with first author).

In an era of systems interventions, using models such as the patient-centered medical home46,47, interprofessional education48 and teamwork training49 to achieve high quality care, a purely disease-oriented approach with attention only to clinical interventions is no longer adequate. Educators can and should take up the challenge to isolate specific training strategies as cost-effective and sustainable interventions for improving health care quality, particularly for chronic diseases. However, the quality of educational research has been shown to be directly associated with study funding29, and we acknowledge that prohibitive cost, noted as a limiting factor in at least one study we assessed36, is one factor limiting implementation of rigorous studies. Some solutions to improve study quality include increasing power with multi-institutional studies similar to those utilized in multicenter clinical trials and the development of multi-institutional shared databases50. For curricula that apply to different health professions (such as cross-cultural communication skills), providers/learners could be combined and results analyzed by subgroups. This approach allows resource management to reduce cost. Curricular standardization and quality control can be better achieved when materials are developed and delivered by expert groups with rigorous peer assessment. Training materials should be based on transparent, evidence-based, reproducible and validated techniques that incorporate attention to baseline competencies. As materials are developed, universal affordable access would be helpful in advancing the field.

In conclusion, we assert that there is a critical need for increased resources to examine education as an independent intervention to improve health outcomes. The same level of planning, attention and scrutiny should be invested in comparative efficacy studies of educational interventions as for clinical and health services research. In light of our findings and proposed algorithm, a modified or new validated tool for evaluating the quality of such studies would be desirable.

Notes

Other terms used for the different databases included “health status disparities,” “health care disparities,” ”education, professional,” “education, medical,” “curriculum,” “internship and residency,” “outcome and process assessment (health care),” “quality, assurance, health care,” “quality indicators, health care,” “health care quality, access and evaluation,” “delivery of health care” and “professional-patient relations.” Also used were the subject headings of “cultural awareness,” “cultural context,” “cultural education,” “cultural literacy,” “culturally relevant education,” “cross-cultural training,” “multicultural education,” “competency-based education,” “outcomes of education,” “outcome-based education,” “curriculum development” and “program evaluation.”

References

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2002:552–593.

US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Healthy People 2010: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives. Washington, D.C.; 2000.

Williams DR, Jackson PB. Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(2):325–334.

Brach C, Fraser I. Can cultural competency reduce racial and ethnic health disparities? A review and conceptual model. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl):181–217.

Smith WR, Betancourt JR, Wynia MK, Bussey-Jones J, Stone VE, Phillips CO, et al. Recommendations for teaching about racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:654–65.

Beach MC, Cooper LA, Robinson KA, et al. Strategies for Improving Minority Healthcare Quality. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 90. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. AHRQ Publication No. 04-E008-02.

Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):560–569.

Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carillo JE, et al. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health an health care. Public Health. 2003;118:293–302.

Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med. 2003;78(6):577–587.

Hobgood C, Sawning S, Bowen J, Savage K. Teaching culturally appropriate care: a review of educational models and methods. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(12):1288–95.

Betancourt J, Green A. Commentary: linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes: perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):583–5.

Beach MC, Gary TL, Price EG, et al. Improving health care quality for racial/ethnic minorities: a systematic review of the best evidence regarding provider and organization interventions. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:104.

Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, et al. Cultural competence: a systematic review of health care provider educational interventions. Med Care. 2005;43:356–73.

Gozu A, Beach MC, Price EG, Gary TL, Robinson K, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes M, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Self-administered instruments to measure cultural competence of health professionals: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):180–90.

Price EG, Beach MC, Gary TL, Robinson KA, Gozu A, Palacio A, Smarth C, Jenckes M, Feuerstein C, Bass EB, Powe NR, Cooper LA. A systematic review of the methodological rigor of studies evaluating cultural competence training of health professionals. Acad Med. 2005;80(6):578–86.

Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, et al. Culturally competent healthcare systems: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Special Issue: Supplement: The guide to community preventive services: Interventions in the social environment to improve community health: A systematic review. 2003;24(Suppl3): 68–79.

Bhui K, Warfa N, Edonya P, McKenzie K, Bhugra D. Cultural competence in mental health care: a review of model evaluations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:15.

Sequist TD, Fitzmaurice GM, Marshall R, Shaykevich S, Marston A, Safran DG, Ayanian JZ. Cultural competency training and performance reports to improve diabetes care for black patients: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):40–6.

Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, et al. Strenghtening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and Elaboration. PloSMed. 2007;4(10):e297.

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1002–9.

Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C, Foster T, Goldmann D, Hall LW, et al. The SQUIRE (standards for quality improvement reporting excellence) guidelines for quality improvement reporting: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(Suppl 1):i13–32.

Schulz KF, Altman DG, CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000251.

Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, Group T. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–6.

Reed D, Price EG, Windish DM, Wright SM, Gozu A, Hsu EB, Beach MC, Kern D, Bass EB. Challenges in systematic reviews of educational intervention studies. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(12 Pt 2):1080–9.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700.

Cochrane library database of systematic reviews. Accessed September 20, 2010 at http://www.thecochranelibrary.com/view/0/AboutTheCochraneLibrary.html#CDSR

BEME database for evidence-based education studies and systematic reviews accessed September 20, 2010 at http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/beme/

Evidence-based medical education ‘clearinghouse.’ Accessed September 20 2010 at http://mededdevelopment.com/evidence.htm.

Little J, Higgins JPT, John PA, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577.

The STROBE checklist available on PLoS Medicine at http://www.plosmedicine.org/. Information on the STROBE Initiative available at http://www.strobe-statement.org, Accessed September 20, 2010.

Boutron I, Dutton S, Ravaud P, Altman DG. Reporting and interpretation of randomized controlled trials with statistically non significant results for outcomes. JAMA. 2010;303:2058–2064.

Mulrow C, Panghorne P, Grimshaw J. Integrating heterogeneous pieces of evidence in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(11):989–95.

Wade P, Berstein B. Cultural sensitivity training and counselor’s race: effects on black female clients’s perceptions and attrition. J Couns Psychol. 1991;38:9–15.

Mazor SS, Hampers LC, Chande VT, Krug SE. Teaching Spanish to pediatric emergency physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:693–695.

Way BB, Stone B, Schwager M, Wagoner D, Bassman R. Effectiveness of the New York State Office of Mental Health Core Curriculum: direct care staff training. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2002;25:398–402.

Majumdar B, Browne G, Roberts J, Carpio B. Effects of cultural sensitivity training on health care provider attitudes and patient outcomes. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36(2):161–6.

Thom DH, Tirado MD, Woon TL, McBride MR. Development and evaluation of a cultural competency training curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:38.

McElmurry BJ, McCreary LL, et al. Implementation, outcomes, and lessons learned from a collaborative primary health care program to improve diabetes care among urban Latino populations. Health Promot Pract. 2009;10(2):293–302.

Hill CLA, MN PNR. Designing and evaluating interventions to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):477–486.

Atkins D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Harbour RT, Hill S, Jaeschke R, Liberati A, Magrini N, Mason J, O'Connell D, Oxman AD, Phillips B, Schünemann H, Edejer TT, Vist GE, GRADE Working Group. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations II: pilot study of a new system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;5(1):25.

Anderson EB. Patient-centeredness: a new approach. Nephrol News Issues. 2002;16:80–82.

Johnson RL, Roter DL, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race and the quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–2090.

Wagner EH, Bennett SM, Austin BT, Greene SM, Vonkorff M, Schaefer JK. Finding common ground: patient-centeredness and evidence-based chronic illness care. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:s7–s15.

Cooper LA, Roter DL, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to enhance patient-physician partnership, patient adherence and high blood pressure control among ethnic minorities and poor persons: study protocol NCT00123045. Implement Sci. 2009;4:7.

Cooper LA, Ford DE, Ghods BK, Roter DL, Primm AB, Larson SM, Gill JM, Noronha GJ, Shaya EK, Wang NY. A cluster randomized trial of standard quality improvement versus patient-centered interventions to enhance depression care for African Americans in the primary care setting: study protocol NCT00243425. Implement Sci. 2010;5:18.

Beal, A. C., Doty, M. M., Hernandez, S. E., Shea, K. K., & Davis, K.. Closing the divide: How medical homes promote equity in health care: Results from The Commonwealth Fund 2006 Health Care Quality Survey. The Commonwealth Fund, 2007, June 27: 62. Accessed September 20, 2010 from http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=506814

Grumbach, K., Bodenheimer, T., & Grundy, P. (2009, August). The outcomes of implementing patient-centered medical home interventions: A review of the evidence on quality, access and costs from recent prospective evaluation studies. Accessed September 20, 2010, from http://familymedicine.medschool.ucsf.edu/cepc/pdf/outcomes%20of%20pcmh%20for%20White%20House%20Aug%202009.pdf

Reeves S, Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Barr H, Freeth D, & Hammick M. Interprofessional education: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2008, article CD002213. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2

Chakraborti C, Boonyasai RT, Wright SM, Kern DE. A systematic review of teamwork training interventions in medical student and resident education. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(6):846–53. Epub 2008 Apr 2.

Gruppen L. Improving medical education research. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(4):331–335.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Linda Murphy, MLIS and Racheline Habousha, MLIS for their assistance in literature search; and to Mary Catherine Beach, MD, MPH, Eboni Price-Haywood, MD, MPH, Barbara J. Turner, MD, MSED, Michael Prislin, MD, and Majumdar Basanti, PhD, for critical review and feedback. This project is supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute: K07HL079256, “An Integrative, Evidence-based Model of Cultural Competency Training in Latino Health across the Continuum of Medical Education” (2004 - 2010, Lie); K07HL079330 “Integrated Immersive Approaches to Cultural Competence” (2005-2009, Bereknyei, Braddock); K07HL792405 “Linking Health Disparities Research to Medical Education” (2004-2010, Gomez); K07HL085472,” Reducing Health Inequities through Medical Education (2006-2011, Lee-Rey). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Consortium for Multicultural Education for Health Professionals (http://culturalmeded.stanford.edu/). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the position or opinions of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 167 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Lie, D.A., Lee-Rey, E., Gomez, A. et al. Does Cultural Competency Training of Health Professionals Improve Patient Outcomes? A Systematic Review and Proposed Algorithm for Future Research. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 317–325 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0