Abstract

We examined whether the addition of community-based accompaniment to Rwanda’s national model for antiretroviral treatment (ART) was associated with greater improvements in patients’ psychosocial health outcomes during the first year of therapy. We enrolled 610 HIV-infected adults with CD4 cell counts under 350 cells/μL initiating ART in one of two programs. Both programs provided ART and required patients to identify a treatment buddy per national protocols. Patients in one program additionally received nutritional and socioeconomic supplements, and daily home-visits by a community health worker (“accompagnateur”) who provided social support and directly-observed ingestion of medication. The addition of community-based accompaniment was associated with an additional 44.3 % reduction in prevalence of depression, more than twice the gains in perceived physical and mental health quality of life, and increased perceived social support in the first year of treatment. Community-based accompaniment may represent an important intervention in HIV-infected populations with prevalent mental health morbidity.

Resumen

Este estudio evaluó si el agregado del acompañamiento comunitario al modelo nacional de tratamiento antirretroviral (TARV) utilizado en Ruanda, se asocia a mejores resultados en la salud psicosocial de los pacientes durante el primer año de tratamiento. Se enrolaron 610 adultos infectados con VIH, con recuento de células CD4 inferior a 350 por microlitro y que iniciaron el TARV en uno de dos programas. Ambos programas proporcionaron tratamiento antirretroviral y, según protocolo nacional, se les solicitó a los pacientes la identificación de un compañero para el tratamiento. En uno de los programas, los pacientes recibieron además: ayuda nutricional y socioeconómica y visitas diarias de agentes sanitarios de la comunidad (acompañadores) que proporcionaron apoyo social y que vigilaron directamente la toma de los medicamentos. El acompañamiento comunitario se asoció a una reducción adicional de 44,3 % en la prevalencia de depresión, a un aumento de más del doble en la calidad de vida física y mental percibida y a un aumento de la percepción del apoyo social durante el primer año de tratamiento. El acompañamiento comunitario puede representar una importante intervención en las poblaciones infectadas por el VIH y con una predominante morbilidad en la salud mental.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Eis C, Boshoff W, Scott C, Strydom W, Joubert G, van der Ryst E. Psychiatric co-morbidity in South African HIV/AIDS patients. SAMJ. 1999;89(9):992.

Gupta R, Dandu M, Packel L, Rutherford G, Leiter K, Phaladze N, et al. Depression and HIV in Botswana: a population-based study on gender-specific socioeconomic and behavioral correlates. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):e14252.

Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Persistence of psychiatric disorders in a cohort of HIV/AIDS patients in South Africa: a 6-month follow-up study. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(4):479–84.

Ciesla JA, Roberts JE. Meta-analysis of the relationship between HIV infection and risk for depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):725–30.

Collins PY, Elkington KS, von Unger H, Sweetland A, Wright ER, Zybert PA. Relationship of stigma to HIV risk among women with mental illness. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(4):498–506.

Meade CS, Sikkema KJ. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(4):433–57.

Maj M, Janssen R, Starace F, Zaudig M, Satz P, Sughondhabirom B, et al. WHO neuropsychiatric AIDS study, cross-sectional phase I. Study design and psychiatric findings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51(1):39–49.

DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101–7.

Low-Beer S, Chan K, Yip B, Wood E, Montaner JS, O’’haughnessy MV, et al. Depressive symptoms decline among persons on HIV protease inhibitors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(4):295–301.

Chan KS, Orlando M, Joyce G, Gifford AL, Burnam MA, Tucker JS, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and improvements in mental health: results from a nationally representative sample of persons undergoing care for HIV in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(1):104–11.

Judd FK, Cockram AM, Komiti A, Mijch AM, Hoy J, Bell R. Depressive symptoms reduced in individuals with HIV/AIDS treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(6):1015–21.

Leserman J, Petitto JM, Golden RN, Gaynes BN, Gu H, Perkins DO, et al. Impact of stressful life events, depression, social support, coping, and cortisol on progression to AIDS. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(8):1221–8.

Leserman J, Petitto JM, Perkins DO, Folds JD, Golden RN, Evans DL. Severe stress, depressive symptoms, and changes in lymphocyte subsets in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. A 2-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(3):279–85.

Antelman G, Kaaya S, Wei R, Mbwambo J, Msamanga GI, Fawzi WW, et al. Depressive symptoms increase risk of HIV disease progression and mortality among women in Tanzania. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(4):470–7.

Ammassari A, Antinori A, Aloisi MS, Trotta MP, Murri R, Bartoli L, et al. Depressive symptoms, neurocognitive impairment, and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(5):394–402.

Hinkin CH, Castellon SA, Durvasula RS, Hardy DJ, Lam MN, Mason KI, et al. Medication adherence among HIV + adults: effects of cognitive dysfunction and regimen complexity. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1944–50.

Ickovics JR, Hamburger ME, Vlahov D, Schoenbaum EE, Schuman P, Boland RJ, et al. Mortality, CD4 cell count decline, and depressive symptoms among HIV-seropositive women: longitudinal analysis from the HIV epidemiology research study. JAMA. 2001;285(11):1466–74.

Starace F, Ammassari A, Trotta MP, Murri R, De Longis P, Izzo C, et al. Depression is a risk factor for suboptimal adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):S136–9.

Muhwezi WW, Agren H, Neema S, Maganda AK, Musisi S. Life events associated with major depression in Ugandan primary healthcare (PHC) patients: issues of cultural specificity. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2008;54(2):144–63.

Ministry of Health (TRAC Plus). Guidelines for the provision of comprehensive care for persons infected by HIV in Rwanda. Kigali: Rwanda Ministry of Health; 2009.

Unge C, Sodergard B, Marrone G, Thorson A, Lukhwaro A, Carter J, et al. Long-term adherence to antiretroviral treatment and program drop-out in a high-risk urban setting in sub-Saharan Africa: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13613.

Birbeck GL, Chomba E, Kvalsund M, Bradbury R, Mang’’mbe C, Malama K, et al. Antiretroviral adherence in rural Zambia: the first year of treatment availability. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(4):669–74.

Binagwaho A, Ratnayake N. The role of social capital in successful adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa. PLoS Med. 2009;6(1):e18.

Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009;6(1):e11.

Wouters E, Van Damme W, Van Loon F, van Rensburg D, Meulemans H. Public-sector ART in the Free State Province, South Africa: community support as an important determinant of outcome. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1177–85.

Mshana GH, Wamoyi J, Busza J, Zaba B, Changalucha J, Kaluvya S, et al. Barriers to accessing antiretroviral therapy in Kisesa, Tanzania: a qualitative study of early rural referrals to the national program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(9):649–57.

Unge C, Johansson A, Zachariah R, Some D, Van Engelgem I, Ekstrom AM. Reasons for unsatisfactory acceptance of antiretroviral treatment in the urban Kibera slum, Kenya. AIDS Care. 2008;20(2):146–9.

Rich ML, Miller AC, Niyigena P, Franke MF, Niyonzima JB, Socci A, et al. Excellent clinical outcomes and high retention in care among adults in a community-based HIV treatment program in rural Rwanda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(3):e35–42.

Franke MF, Kaigamba F, Socci AR, Hakizamungu M, Patel A, Bagiruwigize E, et al. Improved retention associated with community-based accompaniment for antiretroviral therapy delivery in rural Rwanda. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 (in press).

Behforouz HL, Farmer PE, Mukherjee JS. From directly observed therapy to accompagnateurs: enhancing AIDS treatment outcomes in Haiti and in Boston. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 5):S429–36.

Shin S, Munoz M, Zeladita J, Slavin S, Caldas A, Sanchez E, et al. How does directly observed therapy work? The mechanisms and impact of a comprehensive directly observed therapy intervention of highly active antiretroviral therapy in Peru. Health Soc Care Community. 2011;19(3):261–71.

Munoz M, Finnegan K, Zeladita J, Caldas A, Sanchez E, Callacna M, et al. Community-based DOT-HAART accompaniment in an urban resource-poor setting. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):721–30.

Institut National de la Statistique du Rwanda (INSR), ORC Macro. Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Calverton; 2006.

Centre de Traitement et de Recherche sur le SIDA. Guide pour la prise en charge thérapeutique du VIH/SIDA. 2005.

Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, Kaplan BH. The Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire. Measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care. 1988;26(7):709–23.

Wu AW, Revicki DA, Jacobson D, Malitz FE. Evidence for reliability, validity and usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV). Qual Life Res. 1997;6(6):481–93.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:79–110.

Epino HM, Rich ML, Kaigamba F, Hakizamungu M, Socci AR, Bagiruwigize E, et al. Reliability and construct validity of three health-related self-report scales in HIV-positive adults in rural Rwanda. AIDS Care. 2012;24(12):1576–83. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.661840.

Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied longitudinal analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2011.

Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):267–78.

O’’rian RM. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual Quant. 2007;41(5):673–90.

Allen C, Jazayeri D, Miranda J, Biondich PG, Mamlin BW, Wolfe BA, et al. Experience in implementing the OpenMRS medical record system to support HIV treatment in Rwanda. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129(Pt 1):382–6.

Freeman M, Patel V, Collins PY, Bertolote J. Integrating mental health in global initiatives for HIV/AIDS. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:1–3.

Kelly K, Freeman M. Organization and systems support for mental health interventions in anti-retroviral (arv) therapy programmes., Mental health and HIV/AIDS seriesGeneva: World Health Organisation; 2005.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):859–77.

Whetten K, Reif S, Whetten R, Murphy-McMillan LK. Trauma, mental health, distrust, and stigma among HIV-positive persons: implications for effective care. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):531–8.

WHO Regional Office for Africa. WHO Country Cooperation Strategy 2009–2013: Rwanda. 2009.

Riley ED, Neilands TB, Moore K, Cohen J, Bangsberg DR, Havlir D. Social, structural and behavioral determinants of overall health status in a cohort of homeless and unstably housed HIV-infected men. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35207.

Idoko JA, Agbaji O, Agaba P, Akolo C, Inuwa B, Hassan Z, et al. Direct observation therapy-highly active antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting: the use of community treatment support can be effective. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18(11):760–3.

Sarna A, Luchters S, Geibel S, Chersich MF, Munyao P, Kaai S, et al. Short- and long-term efficacy of modified directly observed antiretroviral treatment in Mombasa, Kenya: a randomized trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(5):611–9.

Springer SA, Chen S, Altice F. Depression and symptomatic response among HIV-infected drug users enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Care. 2009;21(8):976–83.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this work was provided by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical Schools. We thank the dedicated teams of research and clinical staff that supported this project and the participants who participated in this study. We also thank Sidney Atwood for assistance with statistical programming; Bethany Hedt-Gauthier for helpful discussion regarding the data analysis plan; and Daniela Colaci, Carmen Contreras, and volunteers at Translators Without Borders for Spanish language translation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Profile Analysis

Continuous outcome estimates (social support score, mental health quality of life score, and physical health quality of life score) for baseline, 6, and 12 months were modeled as:

where health outcomes followed a normal distribution and were a function of a constant term (α), treatment group (trt i ), measurement occasion (time ij ), interaction of treatment group across measurement occasions (trt * time ij ), and a set of covariates (X) with associated vectors of coefficients (β), while ε ij was an error term that varied among individuals (i) and across time (j). These models accounted for repeated measures of individuals with an unstructured covariance matrix.

We conducted a similar analysis to calculate the prevalence of depression, a common binary outcome, except we assumed the outcome followed a Poisson distribution and used a robust variance estimator:

Using the estimated outcomes for each individual and time point from the above models, we estimated expected change of each individual from baseline for all outcomes including depression, and then averaged within treatment groups:

Adjust for Baseline Analysis

Continuous outcome estimates (social support score, mental health quality of life score, and physical quality of life health score) for 6 and 12 months were modeled as:

where health outcomes followed a normal distribution and were a function of a constant term (α), treatment group (trt i ), measurement occasion (time ij ), interaction of treatment group across measurement occasions (trt * time ij ), baseline score (baseline i ), and a set of covariates (X) with associated vectors of coefficients (β), while ε ij was an error term that varied among individuals (i) and across time (j). These models accounted for repeated measures of individuals; because outcomes are modeled at just two time points, a compound symmetry covariance structure was specified.

We conducted a similar analysis to calculate the prevalence of depression, a common binary outcome, except we assumed the outcome followed a Poisson distribution and used a robust variance estimator:

To model change since baseline, we used the following model for all outcomes including depression:

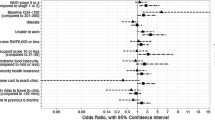

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomson, D.R., Rich, M.L., Kaigamba, F. et al. Community-Based Accompaniment and Psychosocial Health Outcomes in HIV-Infected Adults in Rwanda: A Prospective Study. AIDS Behav 18, 368–380 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0431-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0431-2