Abstract

Aim of the review In low and middle income countries private pharmacies are considered a valuable resource for health advice and medicines in many communities. However the quality of the service they provide has often been questioned and is unclear. This paper reviews the evidence regarding the quality of professional services from private pharmacies in low and middle-income countries. Method A literature search (computer and hand searches) was undertaken to identify all studies which included an assessment of the quality of some aspect of private pharmacy services in low and middle income countries. Results 30 studies were identified which spanned all regions in the developing world. These included 9 which examined the scope and/or quality of a range of professional services, 14 which assessed the quality of advice provided in response to specific symptoms and 7 which investigated the supply of medicines without a prescription. A range of methods were employed, in particular, questionnaire surveys with staff and/or clients and assessment of practice using simulated client methodology. Whilst many authors identified a potential for pharmacies to contribute more effectively to primary health care, virtually all studies identified deficiencies in the quality of current professional practice. In particular authors highlighted the lack of presence of pharmacists or other trained personnel, the provision of advice for common symptoms which was not in accordance with guidelines and the inappropriate supply of medicines. Conclusion The evidence-base regarding the quality of professional services from pharmacies in low and middle income countries is limited, but indicates that standards are often deficient. If pharmacists are to contribute effectively to health care, the barriers to the provision of higher quality care and ways in which these might be overcome must be identified and examined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of findings on practice

-

•

The evidence-base regarding the quality of pharmacy services in low-middle income countries is limited.

-

•

Most studies consistently highlight shortcomings in professional practice in terms of advice-giving and supply of medicines.

-

•

If pharmacy is to contribute more effectively to health care in low and middle income countries, barriers to the provision of higher quality care must be examined and addressed.

Introduction

The role of private pharmacies in contributing to health care, in terms of the provision of health advice and the supply of medicines in low and middle income countries has been a focus of discussion both within and outside the profession for many years [1–4]. Private pharmacies are present in many communities, especially in urban areas, where they are often seen as a convenient ‘first point of call’ for advice on common symptoms and other health problems. They are also often viewed as an underused resource in the provision of health care at a community level [1, 4–8].

A number of barriers to safe and effective health care in low and middle income countries have been identified and extensively discussed in the published literature. Most pertinently these include a lack of access to essential medicines by large numbers of people in the poorest countries and regions, irrational use of medicines in low and middle income countries especially where regulation is limited and there are shortages of health professionals and adequately trained health workers. Over many years the WHO has continuously promoted essential medicines and other programmes to assist countries in developing suitable drug selection and procurement policies to achieve wider access to essential medicines whilst ensuring their quality, efficacy, safety and rational use [9]. However, problems still persist, especially in the poorest regions [10]. The irrational use of medicines has been investigated from the perspective of prescribing by physicians, supplies and recommendations by pharmacies and other medicines outlets, consumers’ use of medicines and health beliefs, and promotion and marketing by the pharmaceutical industry [11–19]. Shortages of health workers, which are most acute in areas where they are arguably most needed is also recognised as a major hindrance to health and pharmaceutical care [5, 20, 21].

Aim of the review

In low-income countries there is a complex range of medicines outlets spanning the formal and informal health sectors which employ different cadres of professional and non-professional, trained and untrained personnel. However, the focus of this review is the supply of medicines from private pharmacies: where a pharmacist is either present or responsible for the services. Thus, the aim of this paper is to review research that has assessed the quality of private community-based pharmacy services in low and middle-income countries. Specific objectives were to establish which aspects of pharmacy services have been examined and the methods that have been employed in these studies, and to provide an assessment of the quality of private pharmacy services.

Methods

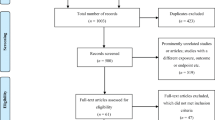

Studies were identified in a systematic review of published research since 1990. Literature searches were conducted on PubMed, MEDLINE, Embase, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts and Pharmline. Keywords for the search included: PHARMACY, PHARMACIST, PHARMACY SERVICES, DEVELOPING COUNTRIES, LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES, MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES AFRICA, ASIA, SOUTH AMERICA. The terms PHARMACY AND PHARMACIST were combined with the names of 35 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and America, including all those in the UKs Department for International Development priority list [22]. In addition hand searches of citations in relevant papers and the contents pages of key journals in the field were performed.

Eligible studies were those which provided an assessment of the quality of some aspect of private pharmacy services in a country commonly considered as low or low-middle income. All eligible papers reported the findings of empirical research and employed a scientific approach. The review focused on private community-based pharmacies for which pharmacists had direct involvement in and/or responsibility for the services provided. Thus studies restricted to drug stores and other medicine-outlets were excluded. Also excluded were intervention studies in which the feasibility or value of a new service (rather than existing services) was the subject of evaluation and papers relying on impressionistic or anecdotal evidence to provide a general commentary.

The analysis focused on firstly, the aims and objectives of the studies to document the range and types of services that had been examined. Secondly the extent to which a scientific approach had been employed was addressed in terms of study design, sampling, data collection and outcome measures. This enabled an assessment of the quality of private pharmacy services taking into account both the extent and the strength of the evidence.

Results

A total of 30 studies were identified (see Table 1). These spanned countries in all regions of the developing world. In Asia studies had been undertaken in Vietnam (7 studies), India (3), Lao PDR (2), Nepal (1) and Thailand (1). In Africa, countries included Nigeria (5), Uganda (2), Egypt (2), Ghana (1), Ethiopia (1), Gambia (1) and Zimbabwe (1). In Central/South America there were 3 studies: Brazil (2) and Mexico (1).

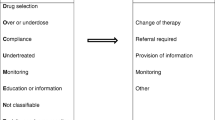

Five studies documented the scope of primary care services provided by private pharmacies and a further four assessed the quality of a range of activities including environmental factors (e.g. cleanliness and storage) dispensing, labelling, advice-giving. The availability and/or supply of medications with or without a prescription were investigated in 7 studies; 6 of these were concerned with antibiotics and one with medications for epilepsy.

Fourteen studies examined the knowledge and or management of specific symptoms and diseases by pharmacy staff. The subjects of these studies were sexually transmitted diseases (6 studies), diarrhoea (3), acute respiratory infections (2), TB (2) and asthma (1). In addition one of the studies investigating the supply of antibiotics without a prescription [36], focused on the management of symptoms of STIs and diarrhoea in children and thus the findings of this study are also included in the relevant analyses relating to the management of symptoms.

The scope and quality of pharmacy services

Five studies Benin City, Nigeria [23, 24]; Alexandria, Egypt [25]; Kampala, Uganda [26]; and Hanoi, Vietnam [27] provided a description of the scope of services provided from pharmacies and the roles of pharmacy staff. Survey methodology involving representative samples of pharmacies (sample sizes: 100–227) was employed in three studies [23–25], and data were collected in self completion questionnaires. This was supplemented, in one case [25] by direct observation, which would allow some assessment of the reliability of self-reports. A case study approach, with data collection over an extended period, was taken in two studies [26, 27]. Each of these studies focused on just two pharmacies, employing a mixture of methods including staff interviews and observation of clients to examine service provision. This approach enables more detailed information to be collected which is from perspective of an independent observer. However, it is labour intensive and thus only small numbers of pharmacies are involved, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

All these studies, whilst confirming an important role in supply of medicines saw some potential for more professional involvement by pharmacists and their staff; in particular, in advising clients about the purchase and use of medicines. The involvement of pharmacists themselves in interacting with clients was found to be small, these activities were commonly reported as being delegated to pharmacy staff.

Four studies (Lao PDR [28, 29], India [30] and Ethiopia [31]) employed a range of methods (questionnaires, interviews with staff and/or clients and observation) to assess the quality of different aspects of pharmacy services. Data were collected in interviews with pharmacy staff, which, in 3 studies, was combined with observations and/or exit interviews with clients. Three of these studies included samples of between 105 and 110 pharmacies, one study 3 pharmacies. Three of the studies also combined different methods of data collection which would enable some validation by comparing data from different sources.

In studies assessing the quality of practice, all identified shortcomings. These related to dispensing activities, labelling, information about the medicines and their use, and advice to clients. Again the lack of presence of pharmacists, or other suitably qualified staff, to assume any direct responsibility for service provision was also highlighted. Studies which included private pharmacies as well as other (non-pharmacy) retail drug outlets suggested that practice in the pharmacies was often not better, except (in one study [31]) with regard to refusals of sale of some prescription-only products.

Sales of medicines without a prescription

Six studies (Vietnam [32], Nepal [33], Nigeria [34], Brazil [35], Zimbabwe [36], Thailand [37]) focused on availability and/or appropriateness of supply of antibiotics, for which problems of resistance are a major public health concern. Methods of investigation included collection of data by interview and questionnaire from pharmacists and clients regarding sales and purchases, and simulated client methodology in which researchers posed as a clients with symptoms of STD, diarrhoea, dysuria, acute respiratory infections, viral gastroenteritis, skin abrasion or rhino-sinusitis. Sample sizes in terms of numbers of pharmacies (between 25 and 800) and/or number of interactions or sales were often large and whilst differing methods of data collection were employed, the findings of these studies were generally consistent. All studies identified questionable practices regarding unauthorised supply and/or concerns over the appropriateness of supply of antibiotics, recommendations of pharmacy staff and/or proposed use by clients. Authors also commented on a lack of compliance of pharmacy staff with guidelines regarding the supply of antibiotics without a prescription.

In a survey investigating the supply of anti-epileptic drugs for which continuity of care is important, data were collected in interviews with staff and by simulated clients. This study revealed variable practices and a need for greater understanding by pharmacy staff of the management of epilepsy [38].

Health-related advice in pharmacies

Symptoms of STI

Seven studies (including one in which the primary focus was the supply of antibiotics) assessed advice and recommendations for symptoms of STIs: Zimbabwe [36], Ghana [39], Vietnam [40], Gambia [41], Brazil [42], Mexico [43] and Nigeria [44]. Simulated clients presenting with symptoms of STIs were employed in 5 studies [36, 39–42]. In four of these studies [36, 39–41], data on the knowledge and usual practices of staff were also collected in interviews or questionnaires. One further study assessed practice by presenting hypothetical case scenarios in interviews with pharmacy staff [43]; and another [44], examined knowledge and practices regarding symptoms of STIs in a structured self-completion questionnaires. In all studies, advice and management were reported to be deficient, with treatment guidelines not being followed. The only study which presented a more positive picture was one relying on self-reporting by pharmacy staff in a structured instrument [44], which is more difficult to validate in terms of whether or not the findings are a true reflection of practice. Studies in which pharmacy staff were interviewed, all concluded that pharmacies were important sources of advice and for people with symptoms of STIs, leading authors to conclude that training of staff in the pharmacy sector should be part of any public health strategy to improve the management of STIs in line with public health goals.

Diarrhoea

Four studies assessed the practices of pharmacy staff in response to simulated clients presenting as carers of children with diarrhoea (Vietnam [45], Egypt [46], Nigeria [47] and Zimbabwe [36]). The studies were conducted in the context of the recommendation that oral rehydration therapy (ORT) should be the first line of management of acute diarrhoea in children. However, with the exception of one study in which antibiotics were found to be rarely supplied without a prescription [36], in all studies ORT was recommended in only a small number of cases, anti-diarrhoeal and or antibiotics commonly being recommended and/or supplied. Authors commented on the lack of adherence to treatment guidelines despite intensive attempts to promote ORT to the public and professionals for the management of acute diarrhoea. One study which interviewed staff about their usual practices in addition to assessing practice using simulated clients reported a high discrepancy between what they said and what they did [47]. The authors attempted to suggest possible reasons for this, such as profit motives and the perceived expectations of mothers/carers.

Acute respiratory infections

Two studies (Uganda [48] and Vietnam [49]) assessed the knowledge and practices of staff in pharmacies and drug stores when advising on symptoms of ARI in children. Data on knowledge and self-reported practices were gathered in questionnaires, although in the latter study this was combined with visits by simulated clients. Knowledge was judged to be poor, antibiotic dispensing was high, and advice-giving and referral were low. Also, large discrepancies between reported behaviours (in questionnaires) and actual practice (visits by simulated clients) were identified; e.g. staff did not ask questions as they claimed and 20% said they would supply an antibiotic, but in practice 83% did so. Staff also did not ask questions of clients as they reported in the questionnaires [49].

Tuberculosis

Two studies (Vietnam [50] and India [51]) interviewed pharmacists and pharmacy owners respectively regarding their knowledge of TB, its management, and their dispensing activities. Both sets of researchers concluded that although there were some deficiencies in knowledge, pharmacists had an important role in supplying medication and that they appeared willing to participate more formally in local TB management programmes.

Asthma

Simulated clients presented symptoms of mild persistent asthma to pharmacies in India [52]. The authors concluded that most did not receive appropriate advice or medication. They concluded that there was a need for interventions to improve the quality of care.

The 14 studies assessing the advice provided for specific symptoms together included often relatively large and locally representative samples of pharmacies in many parts of the world. Data in these studies were gathered by questionnaires (self-completion or completed by a researcher in an interview) and/or using simulated clients (where researchers posing as clients presented symptoms or requested advice according to a predetermined proforma). Simulated client methodology has commonly been employed to assess aspects of the quality of pharmacy services [53, 54]. All methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Interviews may be a more valid method of assessing knowledge than self-completion questionnaires. Self-reported practice (in a questionnaire or interview) may not be an accurate reflection of what actually happens in practice. Simulated client methodology may provide a typical picture of advice provision. However, this is dependent on developing a realistic scenario and presentation in the pharmacy and the careful attention of researchers to recording details of responses. Simulated client methodology does not enable a comprehensive picture of the range of pharmacy services, continuity of care, or their place in supporting health in local communities. It also does not enable an exploration of possible explanations of why practice may be as it is, the perceptions and reasoning of pharmacy staff, or why knowledge is not translated into practice. Some studies in which data were collected by more than one method were able to identify some wider contextual issues. These studies also highlighted discrepancies between knowledge and/or reported behaviours and actual practices.

Discussion

Given that pharmacy services in communities throughout the world are seen as having an extensive role in the provision of health advice and the supply of medicines, a relatively small number of studies assessing the practices of pharmacists and their staff were found. However, studies did span all regions of the world. Also, many of the studies were similar in terms of the approach to, and operation of, the research. This is possibly a reflection of the common public health priorities, concerns regarding the use of medicines and patterns of practice across many low and middle-income countries. It may also be an indication of common expectations regarding the place and operation of pharmacy services throughout the world.

In terms of limitations of this review, firstly it is possible that as part of local service development and policy initiatives some evaluations of pharmacy services may have been carried out, which were not subsequently submitted for publication. Secondly, the aim of this review was to provide an evidence base regarding the quality of professional pharmacy services. In many low and middle income countries there can be a wide range of medicines outlets serving their local communities. In studies evaluating the practices of these suppliers, professional and non-professional sources of medicines are often not distinguished. Thus, there may be studies that fell outside the remit of this review, which might have involved some pharmacists and/or pharmacy services.

Whilst the evidence base regarding the quality of pharmacy services in low and middle income countries is small, there is notable consistency between the findings of different studies. Many researchers concluded that local pharmacies were an important part of health care provision, being a major source of advice and medicines for many people. This led them to suggest that governments should assume a more active role in regulating practice to promote higher standards of care. As a consequence of the extent to which pharmacies were found to be important sources of health advice and medicines, the formal inclusion of pharmacies in major public health programmes was seen by many authors as vital for their success.

In terms of advice-giving with common symptoms and the use of medicines, virtually all studies raised concerns about the quality of services. This included the extent of questioning of clients, accuracy of diagnosis and/or adherence to guidelines or established protocols regarding recommendations and sales of medicines and provision of advice. Thus, local pharmacies were often found not to be contributing as effectively as they should to public health programmes and guidelines, or supporting individual clients to promote the rational use of medicines.

The findings between studies were often consistent. Hence the profession needs to examine the reasons for the poor quality of care that was reported in these studies; and the implications for pharmacy education, professional organisations and pharmaceutical policy. Studies which gathered data using self-completion questionnaires and independent observation highlighted the discrepancies between ‘reported’ and ‘actual’ practices, verifying that knowledge is often not translated into action. Changing and improving professional practice needs to be addressed in the context of a holistic approach that takes into account the systems and organisation of care, regulation, education, processes and operation in the provision and delivery of care and the perspectives of all stakeholders [13, 55–57]. Delivering a high standard of care must be a high priority for the profession. In this respect the goals and aspirations of both policy-makers and the profession coincide.

Achieving an appropriately trained health workforce is a major challenge in the delivery of health care [20]. Many authors in these studies reported the lack of availability of trained staff. Although registered pharmacies and pharmacists are not present in many communities, when they are they should take steps to ensure the quality of care from their pharmacies. Many studies in investigating the supply of medicines from community outlets did not differentiate professional pharmacy services from other sources. Those that did, rarely reported differences in the quality of services. It is important that as a health care profession, the quality of pharmacy services can be distinguished, so they will be viewed as distinctive by others.

It is widely recognised in developing countries that many medicines are supplied without a prescription, and that pharmacies, along with other medicines outlets, are a vital source of medicines for many people [58]. To ensure rational use of medicines, pharmacy staff need to engage with their clients to ensure that purchases are appropriate to their needs and that other relevant information and advice is also provided.

Conclusion

The evidence-base regarding the quality of professional services from pharmacies in low and middle income countries is very small, especially when the extent of pharmacy services in providing health advice and medicines in many communities throughout the world is taken into account. Most of the studies that have been conducted have consistently highlighted shortcomings in professional practices in terms of advice-giving and the supply of medicines.

If pharmacy is to contribute more effectively to health care the barriers to the provision of higher quality care and ways in which these might be overcome must be identified and examined. In this endeavour, the profession would benefit from a more comprehensive and substantial research and evidence-base. This would provide greater opportunity for the examination and development of professional services in the context of the diverse settings, policy and health priorities in different places in the world. It would also help ensure that examples of good practice, where these exist also feature in the literature.

References

World Health Organisation. The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. Geneva: WHO; 1994. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1994/WHO_PHARM_94.569.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

World Health Organisation. Good Pharmacy Practice. Guidelines in community and hospital settings. Geneva: WHO; 1996. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/WHO_PHARM_DAP_96.1.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

FIP. Standards for quality of pharmacy services. International Pharmaceutical Federation; 1993. Available at http://www.fip.ul/www/uploads/?page=statements. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

World Health Organisation. The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication. Geneva: WHO; 1998. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1998/WHO_DAP_98.13.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

Owusu-Daaku FTK. Pharmacy in Ghana’s health care system: which way forward? Ghana Pharm J. 2002;25:20–3.

Smith FJ. Community pharmacy in Ghana: enhancing the contribution to primary health care. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:234–41. doi:10.1093/heapol/czh028.

Kumari RP, Raman R, Sharma T. Physicians, pharmacists, and people with diabetes in India. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:750–2. doi:10.1007/s11096-008-9225-4.

Yousef AMM, Al-Bakri AG, Bustanji Y, Wazaify M. Self-medication practices in Jordan. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:24–30. doi:10.1007/s11096-007-9135-x.

World Health Organisation. The essential medicines concept: from its beginning until today. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1994/WHO_EDM_2004.3.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

UN Millenium Project. Prescription for healthy development: access to essential medicines. London: Earthscan; 2005. ISBN 1 84407 227-4.

Van der Geest S. The illegal distribution of Western Medicines in developing countries. Med Anthropol. 1982;6:197–219.

Van der Geest S. Pharmaceuticals in the third world: the local perspective. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25:273–6. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(87)90230-9.

Fabricant SJ, Hirschhorn N. Deranged distribution, perverse prescription, unprotected use: irrationality of pharmaceuticals in the developing world. Health Policy Plan. 1987;2:204–13. doi:10.1093/heapol/2.3.204.

Le Grand A, Hogerzeil HV, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM. Interventional research in rational use of drugs: a review. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14:89–102. doi:10.1093/heapol/14.2.89.

Preux PM, Tiemagni F, Fodzo L, Kandem P, Ngouafong P, Ndonko F, et al. Antiepileptic therapies in the Mifi province in Cameroon. Epilepsia. 2000;41:432–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00185.x.

Smith FJ. Pharmacy in developing countries. In: Harding G, Taylor K, editors. Pharmacy practice: chapter 6. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 2001. ISBN 0 415 27159 2.

Goodman C, Brieger W, Unwin A, Mills A, Meek S, Greer G. Medicine sellers and malaria treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: what do they do and how can their practice be improved? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77(supplement):213–8.

Buabeng KO, Duwiejua M, Matowe LK, Smith F, Enlund H. Availability and choice of anti-malarials at medicine outlets in Ghana: the question of access to effective medicines for malaria control. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:613–9. doi:10.1038/clpt.2008.130.

Holloway K. Promoting rational use of medicines. International Network for the Rational Use of Drugs. INRUD News, July 2008. Available at: http://www.inrud.org/documents/upload/vol16no1.pdf Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

World Health Organisation. The World health report 2006: working together for health. Geneva: WHO; 2006. ISBN: 92 4 156 317 6.

Wuliji T. Global pharmacy workforce and migration report: a call for action. Int Pharm J. 2006;20:2–4.

DFID. Priority countries. London: Department for International Development; 2008. Available at: http://www.dfid.gov.uk/africa. Accessed 25 Feb 2009.

Oparah AC, Arigbe-Osula EM. Evaluation of community pharmacists’ involvement in primary health care. Trop J Pharm Res. 2002;1:67–74.

Oparah CA, Enato EFO, Odili UV, Aghomo OE. Activities of community pharmacy counter staff in Benin City, Nigeria. J Soc Adm Pharm. 2002;19:141–4.

Benjamin H, Motawi A, Smith F. Community pharmacists in primary health care in Alexandria. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1995;12:3–11.

Anyama N, Adome RO. Community pharmaceutical care: an 8-month critical review of two pharmacies in Kampala. Afr Health Sci. 2003;3:87–93.

Chuc NTK, Tomson G. ‘Doi moi’ and private pharmacies: a case study on dispensing and financial issues in Hanoi, Vietnam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;55:325–32. doi:10.1007/s002280050636.

Stenson B, Syhakhang L, Eriksson B, Tomson G. Real world pharmacy: assessing the quality of private pharmacy practice in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:393–404. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00142-8.

Syhakhang L, Stenson B, Wahlstrom R, Tomson G. The quality of public and private pharmacy practices: a cross-sectional study in the Savannakhet province, Lao PDR. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57:221–7. doi:10.1007/s002280100295.

Basak SC, Arunkumar A, Masilamani K. Community pharmacists’ attitudes towards use of medicines in rural India. International Pharmacy Journal 2002; 32–5.

Abula T, Worku A, Thomas K. Assessment of the dispensing practices of drug retail outlets in selected towns, North West Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2006;44:145–50.

Duong DV, Binns CW, Le TV. Availability of antibiotics as over-the-counter drugs in pharmacies: a threat to public health in Vietnam. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:1133–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-213.x.

Wachter DA, Joshi MP, Rimal B. Antibiotic dispensing by drug retailers in Kathmandu, Nepal. Trop Med Int Health. 1999;4:782–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00476.x.

Oladipo OB, Lamikanra A. Patterns of antibiotic purchases in community pharmacies in South Western, Nigeria. J Soc Adm Pharm. 2002;19:33–8.

Volpato DE, de Souza BV, Rosa LGD, Melo LH, Daudt CAS, Deboni L. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;3:288–91.

Nyazema N, Viberg N, Khoza S, Vyas S, Kumaranayake L, Tomson G, et al. Low sales of antibiotics without a prescription: a cross-sectional study in Zimbabwean private pharmacies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:718–26. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm013.

Apisarnthanarak A, Tunpornchai J, Tanawitt K, Mundy LM. Nonjudicious dispensing of antibiotics by drug stores in Pratumthani, Thailand. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:572–5. doi:10.1086/587496.

Mac TL, Le VT, Vu AN, Preux PM, Ratsimbazafy V. AEDs availability and professional practices in delivery outlets in a city centre in Vietnam. Epilepsia. 2006;47:300–4. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00425.x.

Mayhew S, Nzambi K, Pepin J, Adjei S. Pharmacists’ role in managing sexually transmitted infections: policy issues and options for Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16:152–60. doi:10.1093/heapol/16.2.152.

Chalker J, Chuc NTK, Falkenberg T, Do NT, Tomson G. STD management by private pharmacies in Hanoi: practice and knowledge of drug sellers. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:299–302. doi:10.1136/sti.76.4.299.

Leiva A, Shaw M, Paine K, Manneh K, McAdam K, Mayaud P. Management of sexually transmitted disease in urban pharmacies in The Gambia. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12:442–52. doi:10.1258/0956462011923471.

Ramos MC, da Silva RDC, Gobbato RO, da Rocha FC, de Lucca G, Vossky J, et al. Pharmacy clerks’ prescribing practices for STD patients in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15:333–6. doi:10.1258/095646204323012832.

Turner AN, Ellertson C, Thomas S, Garcia S. Diagnosis and treatment if presumed STIs at Mexican pharmacies: survey results from a random sample of Mexico City pharmacy attendants. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:224–8. doi:10.1136/sti.79.3.224.

Erhun WO. Management of sexually transmitted diseases in retail drug outlets in Nigeria. J Soc Adm Pharm. 2002;19:145–50.

Van Duong D, Le TV, Binns CW. Diarrhoea management by pharmacy staff in retail pharmacies in Hanoi Vietnam. Int J Pharm Pract. 1997;5:97–100.

Benjamin Sokar-Todd H, Smith FJ. Management of diarrhoea at community pharmacies in Alexandria, Egypt. J Soc Adm Pharm. 2003;20(1):32–8.

Igun UA. Reported and actual prescription of oral rehydration therapy for childhood diarrhoeas by retail pharmacists in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39:797–806. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)90041-8.

Tumwikirize WA, Ekwaru PJ, Mohammed K, Ogwal-Okeng JW, Aupont O. Management of acute respiratory infections in drug shops and private pharmacies in Uganda: a study of counter-attendants’ knowledge and reported behaviour. East Afr Med J. 2004;81(supplement):S33–40.

Chuc NT, Larsson M, Falkenburg T, Do NT, Binh NT, Tomson GB. Management of childhood infections at private pharmacies in Vietnam. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:1283–8. doi:10.1345/aph.10313.

Rajeswari R, Balasubramanian R, Bose SC, Rahman SF. Private pharmacies in tuberculosis control: a neglected link. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:171–3.

Lonnroth K, Lambregts K, Nhien DTT, Quy HT, Diwan VK. Private pharmacies and tuberculosis control: a survey of case detection skills and reported anti-tuberculosis drug dispensing in private pharmacies in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:1052–9.

Van Sickle D. Management of asthma at private pharmacies in India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10:1386–92.

Madden JM, Quick JD, Ross-Degnan D, Kafle KK. Undercover care-seekers: simulated clients in the study of health provider behaviour in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1465–82. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00076-2.

Watson MC, Norris P, Granas AG. A systematic review of the use of simulated patients and pharmacy practice research. Int J Pharm Pract. 2006;14:83–93. doi:10.1211/ijpp.14.2.0002.

Cerderlof C, Tomson G. Private pharmacies and health sector reform in developing countries—professional and commercial highlights. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1995;12:101–11.

Gastelurrutia MA, Benrimoj SIC, Castrillon CC, Casado de Amezua MJ, Fernandez-Llimos F, Faus MJ. Facilitators for practice change in Spanish community pharmacy. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31:32–9.

Babar ZUD, Jamshed S. Social Pharmacy strengthening clinical pharmacy: why pharmaceutical policy research is needed in Pakistan. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:617–9. doi:10.1007/s11096-008-9246-z.

Benjamin H, Smith FJ, Motawi A. Drugs supplied, with and without a prescription from a conurbation in Egypt. East Mediterr Health J. 1996;2:506–14.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Joann Hong for her assistance in the literature searching and data extraction for this review.

Funding

No external sources of funding for this work were obtained.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, F. The quality of private pharmacy services in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Pharm World Sci 31, 351–361 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-009-9294-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-009-9294-z